The United States is committed to conservation. Now, how do we do it?

When the U.S. government committed last January to conserving 30 percent of the United States’ natural land and water by the year 2030, the decision was embraced by the majority of Americans. A poll found that 80 percent of voters supported what’s known as the “30 by 30 plan,” but questions remain about how to decide which pieces of nature should be protected to reach that goal.

Sarah Saunders, MSU adjunct scholar and senior manager of quantitative science at the National Audubon Society. Courtesy photo

Now, Michigan State University ecologists are part of a team that’s sharing data to help inform those choices throughout the United States and beyond. Their research identified North America’s climate change refugia, habitats that will be the most likely to support the persistence of the greatest amount of biodiversity in the face of a changing climate.

The team also included researchers at the National Audubon Society, the University of East Anglia in England and James Cook University in Australia. They released their work Jan. 11 in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

“We know climate change is happening,” said Mariah Meek, an assistant professor in the Department of Integrative Biology (IBIO) in MSU’s College of Natural Science (NatSci) and a faculty affiliate of the Ecology, Evolution and Behavior program. “We wanted to take a forward-looking approach and find where the opportunities are to protect species that will still be able to inhabit their spaces in the future.”

MSU Assistant Professor Mariah Meek, NatSci Department of Integrative Biology. Courtesy photo

The team started with a collection of data and computer models that represent North America’s undeveloped land in the context of its biodiversity. With that information, the researchers accounted for more than 135,000 different species of plants, birds, fungi, reptiles, mammals, amphibians and invertebrates. For the land component, the data enabled researchers to break down the United States, Canada and Mexico into square patches that were 20 km, or roughly 12 miles, across.

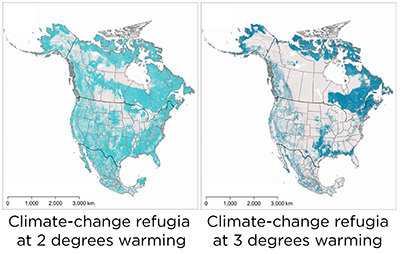

The researchers could then project how well those different patches would continue supporting their current species over the next several decades under four different warming scenarios: scenarios in which the average global temperature increases by 1.5, 2, 3 and 4 degrees Celsius.

This let the team identify the most resilient areas — the refugia — and compare those with currently protected areas, revealing opportunities to expand those protections.

“We still have ample opportunity to protect climate change refugia at this point, if we can limit warming to 2 degrees,” said Sarah Saunders, a senior manager of quantitative science at Audubon and the first author of the new research. Saunders was previously a postdoctoral researcher at MSU and is also currently an IBIO adjunct scholar.

MSU researchers helped create maps of North America showing where habitats known as climate change refugia exist that would be resilient to different warming scenarios. The opportunities to protect these habitats is much greater when we can limit warming. Credit: Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment

“Currently, less than 15 percent of refugia are protected, which surprised me,” Saunders said. “There’s a clear path forward for protecting refugia.”

“If we can protect those areas, those refugia, we’ll be covering a lot of species and improving chances for persistence into the future,” Meek added. But both she and Saunders emphasized the need to keep warming below that 2-degree threshold.

“The difference between under 2 degrees and over 2 degrees is stark. You would hope that it wouldn’t be, but it is,” Meek said. “It’s almost this tipping point where things start to get really bad and our opportunities diminish.”

For example, the team found that at least half of the unprotected natural land in 31 U.S. states would qualify as refugia if warming is kept at or below 2 degrees Celsius. At 3 degrees, 27 states are eliminated from that list, leaving only four.

The western U.S. and mountains, like those found in Colorado, are home to a large area of refugia for terrestrial biodiversity. Credit: Lyndsey Dulfer/Unsplash

At higher temperatures, plants and fungi, which provide food for larger organisms and are critical to ecosystem functioning, are hit especially hard. Another troubling feature in higher warming scenarios is the mismatching of refugia. For example, the places where reptiles and amphibians are best protected aren’t the same as the places where the invertebrates they eat will survive.

“That has cascading effects, and it’s concerning,” Saunders said. “We’re not at that tipping point yet, but we’re getting close.”

“I think this paper is a wake-up call,” Meek said.

Still, she and Saunders stressed that we have the power to limit warming to 2 degrees through personal choices, collective actions and new policies that put an emphasis on protecting the planet. Humanity has the desire, as evidenced by the 30 by 30 initiative in the United States, which itself is part of a larger global movement.

“The opportunities are there, and 30 by 30 is a great initiative, if we can go about it in a science-informed way,” Saunders said. “This research is one guide for doing that.”Banner image: The western United States and mountains, such as those found in Colorado, are home to a large area of refugia for terrestrial biodiversity. Credit: Lyndsey Dulfer/Unsplash