Don’t bank on seed banks to save the grasslands

Article Highlights

- A recent study by MSU plant biologist Lauren Sullivan challenges the assumption that soil seed banks can act as a “biodiversity reservoir” in grasslands.

- The study found that when global change factors such as nutrient additions and herbivore removal are acting on grasslands, the seed bank also decreases in diversity.

- The results suggest that other measures may be needed to help preserve and restore biodiversity in grasslands, such as planting grassland strips around farmland.

As biodiversity loss wreaks havoc on grasslands throughout the world, many have hoped that soil seed banks, or seeds stored in the soil waiting to sprout, would act as a “biodiversity reservoir” and preserve species that are disappearing aboveground. However, a recent study published in Nature Communications by Michigan State University plant biologist Lauren Sullivan and her team challenges that assumption.

MSU Assistant Professor Lauren Sullivan collecting seeds from virgin tall grass at Tucker Prairie in Callaway County, Mo. Credit: Melody Kroll

“We were hoping that the seedlings would be this cryptic reservoir of diversity, but we found that when global change factors such as nutrient additions and herbivore removal are acting on grasslands, that was not the case. The seed bank also decreases similarly in diversity,” said Sullivan, assistant professor in the College of Natural Science’s Department of Plant Biology and a W. K. Kellogg Biological Station and Ecology, Evolution and Behavior Program faculty member. “These factors are not just affecting the aboveground communities but also the belowground communities.”

Grasslands are important because they support grazing, wildlife habitat, carbon sequestration, and of course, agriculture. However, because much of the world’s grasslands have disappeared, they are considered the most endangered ecosystem on the planet. With the rapid advancement of agriculture and other global changes, nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus are much more abundant in the air and soil, and native grassland herbivores are declining.

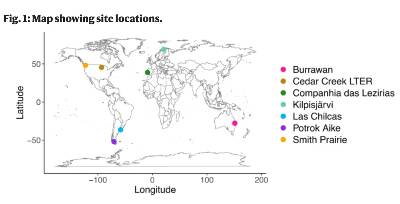

A map showing the seven global grassland sites that contributed to this work. Credit: Lauren Sullivan

To determine how the loss of herbivores and existence of excess nutrients are affecting seed bank communities, Sullivan and her team plugged into the global research cooperative Nutrient Network (NutNet). With 130 grassland sites around the globe, the grassroots research network is studying external threats to the endangered ecosystem.

In 2015, Sullivan and her colleague Anu Eskelinen from the University of Oulu, Finland began recruiting other researchers for their experiment. Once established, the team collected seed bank samples at seven NutNet sites varying in climate, environment, and productivity, on four different continents ranging from a tundra grassland in Finland to a grassland in Argentina. They cut out four cores of soil per plot, put them on trays in a greenhouse, and waited for the seeds to germinate so they could identify and count them. Afterward, the samples went through a dormancy period to make sure nothing else sprouted. This whole process took several years.

Previous studies have shown that fertilization can lead to biodiversity loss in the aboveground community, but this is the first multi-site study to show a link to the seed bank community. In addition, they found that in more homogenous communities, removing herbivores that eat plants can contribute to diversity loss.

Seedbank plots growing in the greenhouse. In the foreground are plots where seedlings are waiting to be removed, and in the background, plots have seedlings identified and removed. Credit: Lauren Sullivan

Herbivores can help spread and make room for plant species that are already present in the aboveground and belowground communities. So, in grasslands the presence of herbivores can add to the biodiversity, but when removed, herbivores can affect the area’s biodiversity by decreasing the growth and spread of fewer species of plants.

The results of this study are concerning and have led to more unanswered questions. Sullivan’s team has already begun working on a broader range experiment with the Disturbance and Recovery Across Global Grasslands Network or DRAGNet, a new global research network and an offshoot of NutNet. By scaling up, taking what they learned, and implementing it at 35 sites, they hope to find more answers.

While seed banks may not be able to protect biodiversity in the grasslands when nutrient enrichment is high, other measures may be taken to help preserve and restore biodiversity. Some researchers have had initial success planting grassland strips around farmland to buffer soil loss and nitrogen and phosphorus erosion and runoff.

“What we found is that preservation of the grasslands undergoing nutrient enrichment probably won’t happen naturally from the seed bank, so in order to add biodiversity to an area, you would have to introduce new seeds yourself,” Sullivan said.Banner image: One seedbank plot with germinating seeds growing from the Cedar Creek, Minn. site. Credit: Katie Schroeder