Keeping bacteria at bay on grilling day

Article Highlights

- One in six people become sick from foodborne illness, resulting in more than 128,000 hospitalizations in the United States every year.

- By following food safety guidelines, you can avoid foodborne illness during grilling season (and beyond).

- Michigan State University expert Shannon Manning, who studies bacteria associated with foodborne illness, such as E. coli, salmonella and Campylobacter jejuni, shares some tips to stay healthy and to stop the spread of antibiotic resistance

Summer is the time for grilling, but as cooking moves from the kitchen to the patio, unwelcome bacterial guests can tag along for dinner.

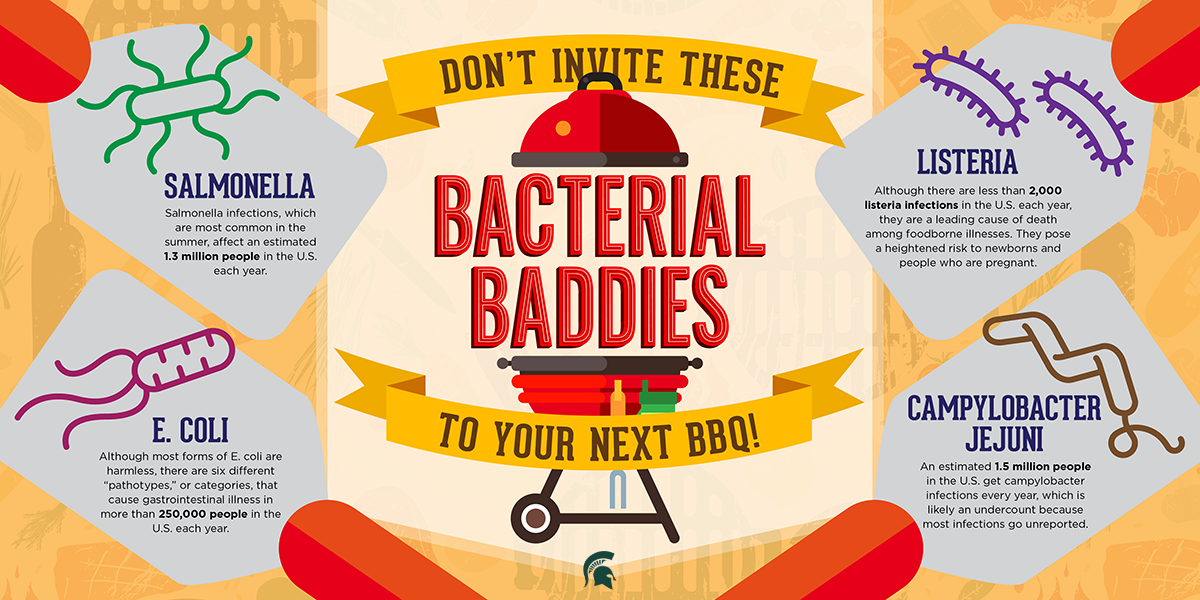

While most bacteria are actually beneficial, certain germs can grow on food and cause foodborne illness, or food poisoning, when eaten. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates 48 million people are sickened by foodborne bacteria every year.

Most illnesses result in minor, flu-like symptoms, including upset stomach, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, fever and dehydration. But some illnesses can result in hospitalization and even death.

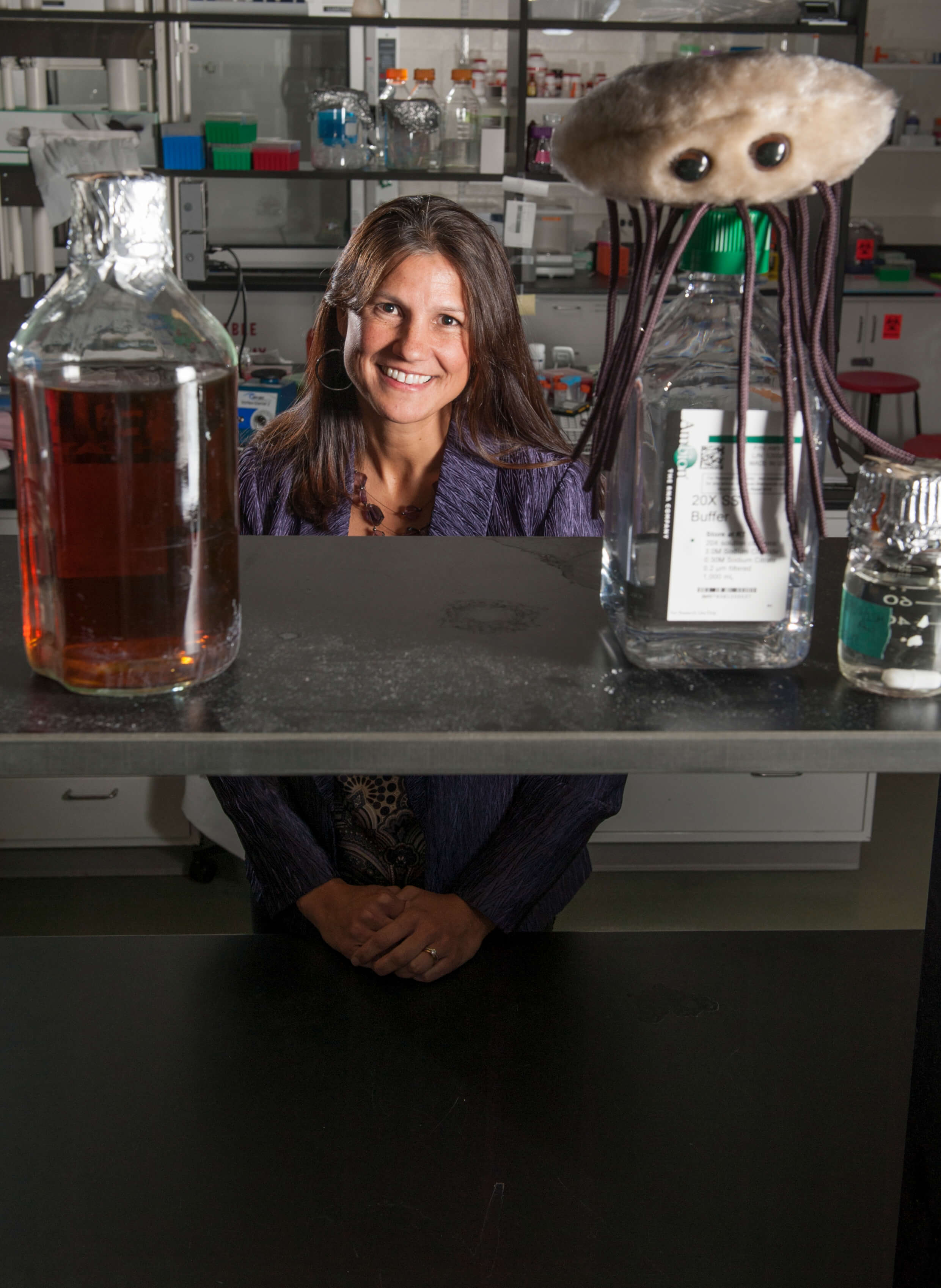

Now, researchers like Shannon Manning, an MSU Research Foundation Professor in the Department of Microbiology, Genetics and Immunology, are showing foodborne illnesses pose another threat: They’re spreading antibiotic resistance.

With grilling season in full swing, the College of Natural Science took this opportunity to catch up with Manning to discuss the harmful bacteria that can ruin a summer party.

The following discussion has been edited for length and clarity.

College of Natural Science: How big of a problem is foodborne illness in Michigan and the U.S. in general?

Shannon Manning: About one in six Americans are sickened by food poisoning every year. The old, young, immunocompromised and pregnant patients are the most susceptible. According to the CDC, foodborne illness hospitalizes about 128,000 people every year, resulting in 3,000 deaths.

The CDC maintains a surveillance program called FoodNet, which separates the country into ten regions. FoodNet tracks 31 different disease-causing bacteria that can be transmitted through food products in the ten regions to identify hot spots for disease and emerging infections.

FoodNet represents only 15% of the U.S. population so Michigan is not surveilled directly. The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services does monitor foodborne illness and has determined that the rates in the state mirror the FoodNet sampling of the upper Midwest region. Because Michigan may have unique features relative to other states, it is important to continue to monitor these infections at the state level as well.

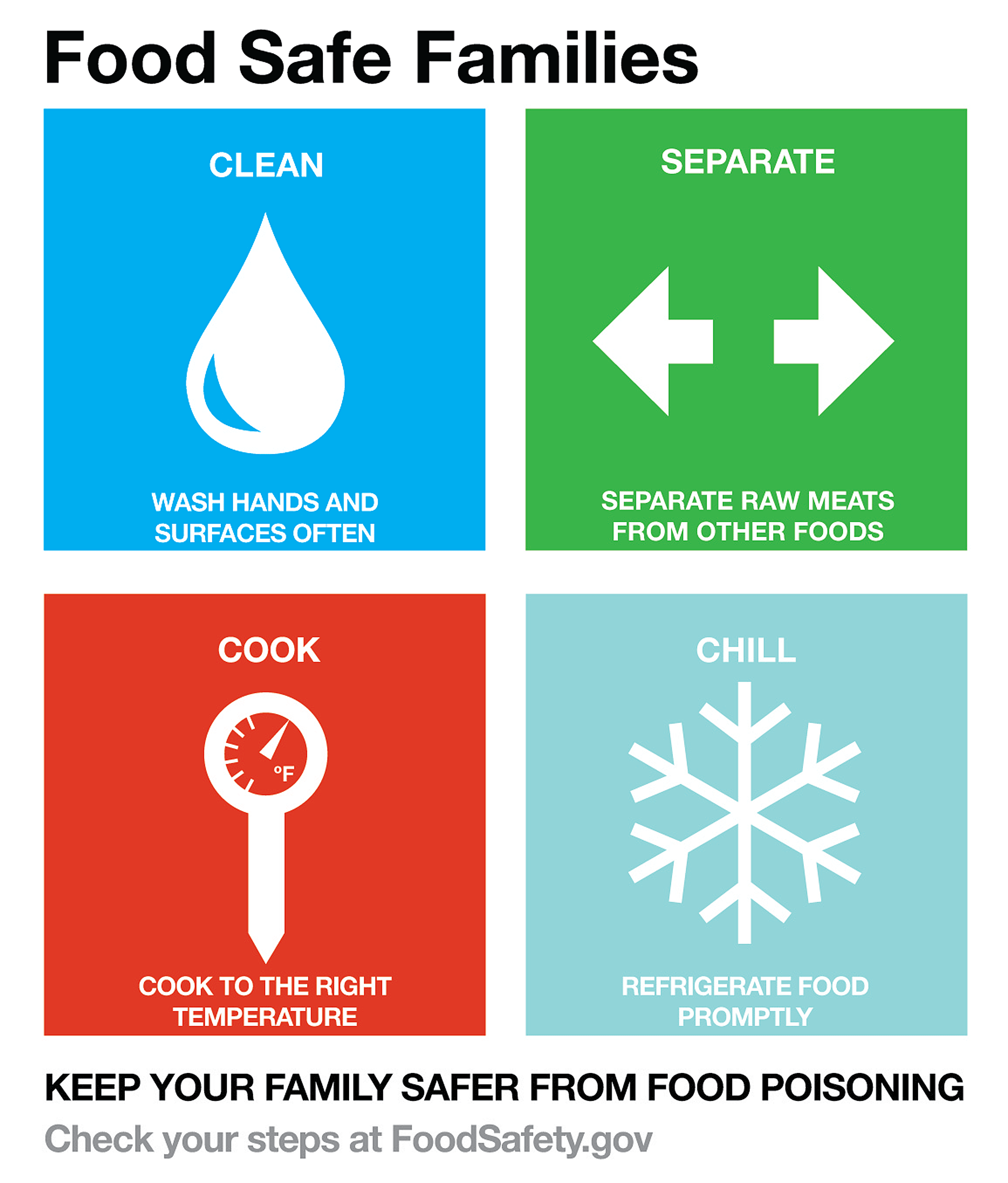

How can people protect themselves from foodborne illness?

It is important to follow simple food safety practices that are recommended by the FDA.

Clean: Wash your hands before, during and after cooking. Wash the outside rind of fruits and vegetables, including melons, before cutting.

Separate: Use different cutting boards, knives and utensils for meat and vegetables to avoid cross contamination. Use different plates and utensils for raw and cooked meat.

Cook: Cook meat to the proper minimum internal temperature.

Chill: Transport foods in an insulated cooler and store leftovers in shallow containers in the refrigerator or freezer

How does the public’s perception of foodborne bacteria match with reality?

In 2018, the Pew Research Center released a report that examined the public’s perception of food safety, especially regarding the use of antibiotics in food animals and genetically-modified foods. They found that one-third of respondents were concerned by the use of antibiotics in animals and pesticides on plants. I was surprised this number was so low.

In reality, we are really concerned about antibiotic use in livestock. If you give livestock antibiotics, the pathogenic, or disease-causing, bacteria could acquire or harbor resistance genes.

These genes allow the bacteria to evade the effects of antibiotics and survive in the food products like meat, which can get transmitted to consumers. The FDA and the World Health Organization have implemented new guidelines that limit the use of certain antibiotics in food animals, especially those that are considered clinically important to treat human infections.

Can you tell us a little bit about what you work on in your lab?

In my lab, we are looking for and characterizing the bacterial foodborne pathogens that most commonly affect human patients.

For example, we are analyzing the genome sequences to understand which bacterial traits are most important for human infections and which may be needed for survival in livestock or poultry. Some of these bacteria are restricted to specific environments or reservoir species like cattle, whereas others have the ability to survive in food products to cause human infections.

How do foodborne bacteria develop resistance to the antibiotics used to treat human illness?

Bacteria that possess certain resistance genes or acquire specific mutations can develop resistance allowing them to survive in the presence of some antibiotics. These resistance genes can be shared with other bacteria in a process called horizontal gene transfer.

Some resistance genes are very specific to one antibiotic, but others can resist multiple antibiotics.

Many of the bacterial foodborne pathogens that cause the highest rates of disease are increasingly becoming resistant to various antibiotics. This is problematic for patients with foodborne infections because the antibiotics commonly used to treat these infections are no longer effective.

Both salmonella and campylobacter — two disease-causing bacteria — are very good at acquiring resistance genes in the environment, and both have been placed on the CDC watchlist of antibiotic resistance threats in the United States.

Campylobacter is the disease-causing bacteria most commonly associated with diarrheal illness, but these illnesses are rarely reported. How can this pathogen successfully stay under the radar compared to illnesses caused by salmonella and E. coli?

People who become ill from eating food contaminated with campylobacter often do not feel sick enough to seek medical care. If they don’t seek care, then a stool sample would not be collected for culture and testing. This lack of testing means that we are likely underestimating the number of these infections.

Even if a stool is collected, campylobacter is very difficult to culture in the laboratory. Without a culture, clinicians cannot make a final diagnosis regarding the cause of the illness.

Other tools are now being used to detect bacterial DNA, proteins or antigens to determine if this bacterium is the cause of the illness. This process is necessary to begin an investigation to track down the source of the infections and determine whether it is part of an outbreak.

Foodborne illness is preventable. By following food safety practices, you can stop harmful bacteria from growing in food as well as contaminating different foods and surfaces in your kitchen. Whether you are hosting a party or simply preparing a daily meal, make sure you follow safe food practices.

- Food safety begins in the grocery store. Purchase meat and poultry right before checking out to ensure these items remains cold. After arriving home, separate meat, poultry, vegetables and fruits. Refrigerate perishable items and freeze poultry and ground meat that will not be used in one to two days.

- Place thawing meat on a plate in the refrigerator to prevent drippings from contaminating the shelves or other items.

- Many recipes call for a marinade, or soaking meat in a savory acidic sauce for several hours. This process tenderizes and adds flavor to meat prior to grilling. Always marinate meat and poultry in the refrigerator. If you plan to use some of marinade as a sauce during grilling, reserve some marinade before adding the raw meat and store it in the refrigerator. Otherwise, boil the used marinade for a few minutes to kill any potential harmful bacteria in the sauce before using it when grilling.

- To prevent cross-contamination or the transfer of harmful bacteria from one food to another or to other surfaces, wash hands before and after handling raw meat and follow by sanitizing surface areas. Do not wash raw meat because this can increase the spread of harmful bacteria.

- Wash fresh fruits and vegetables. Use separate, clean cutting boards and utensils for fruits and vegetables and meat.

- Refrigerate meat until you are ready to begin grilling.

- Cook meat to the designated safe minimum internal temperature to destroy harmful bacteria.

Check the internal temperature of meat with a food thermometer. The safe minimum internal

temperature for different food products is provided below.

- Poultry (whole, ground and breasts): 165°F

- Hamburger (ground beef): 160°F

- All cuts of pork: 160°F

- Beef, veal and lamb as steak, roasts or chops: 145°F (medium rare; let rest 3 minutes), 160°F (medium)

- Use clean platters and tools to separate cooked items from raw, uncooked meat. Keep cooked food hot at about 140°F or warmer until you serve.

- Refrigerate leftovers in shallow containers and throw away any food left at room temperature for more than two hours

Source: FDA and USDA Food Safety Inspection Service

Smoking is another cooking method that is becoming increasingly popular. It is important to use a thermometer to ensure the temperature within the smoker stays between 225 and 300°F throughout the cooking process. Before removing meat from a smoker, use a food thermometer to ensure it has reached a safe internal temperature.

Pit roasting is another cooking method where meat is cooked in a large hole dug in the ground. The fire should be made with hardwood that condenses in volume to fill half the pit with coals after about four to six hours. The cooking process can take up to 12 hours. Before removing the meat from the pit, use a food thermometer to ensure the meat has reached a safe minimum internal temperature.

Source: FDA and USDA Food Safety Inspection Service

The USDA maintains a meat and poultry hotline — 1-888-MPHotline (1-888-674-6854). Experts are available Monday to Friday from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. ET to answer food safety questions in English or Spanish. Recorded food safety messages are available throughout the day.

- Categories: