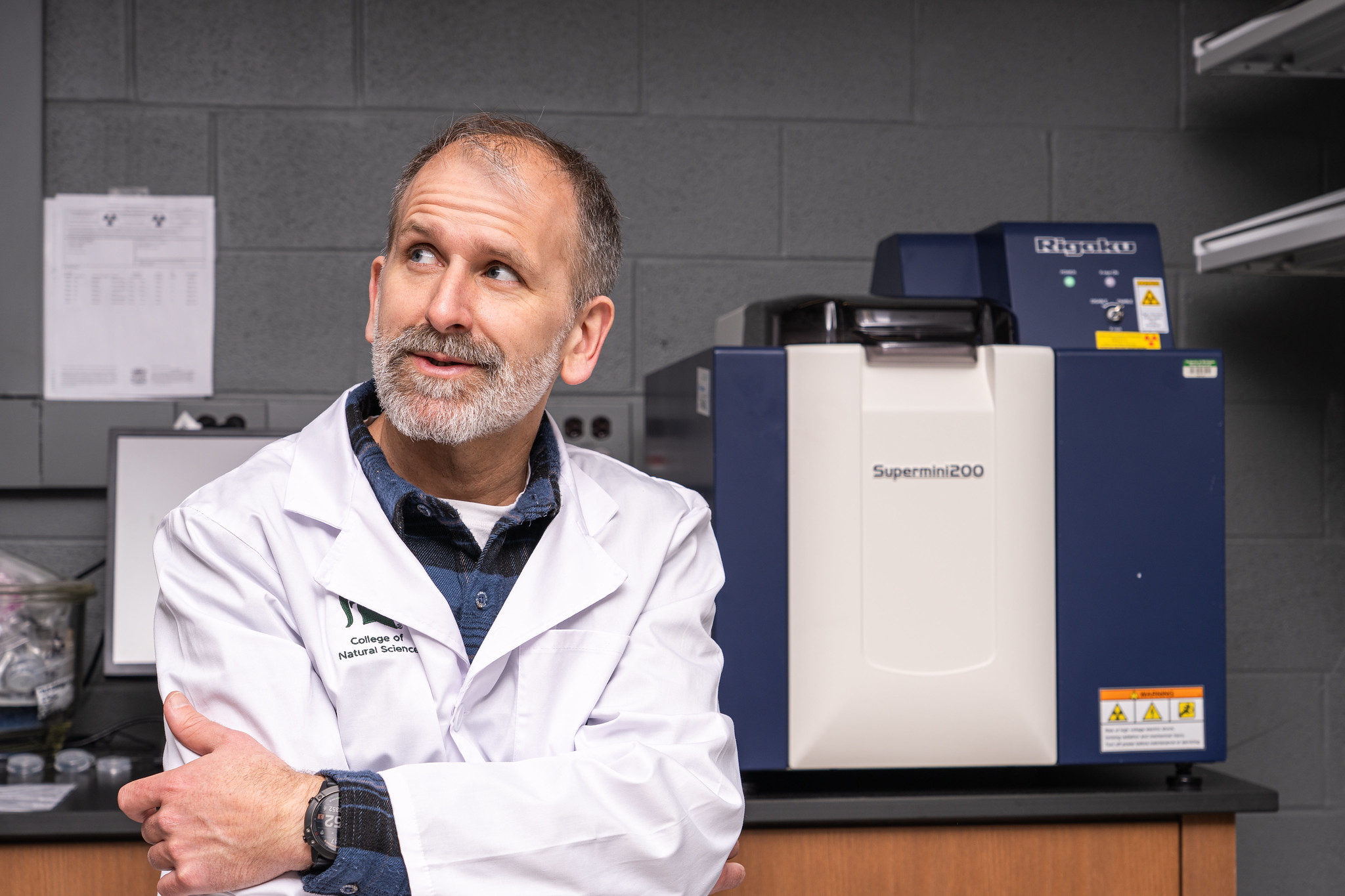

MSU's own rock detective

Earth and environmental sciences professor searches for clues to why continents break apart

Photo credit: Finn Gomez

Millions of years ago, nearly all of Earth’s continents were fused together in one giant land mass called Pangea. That is, until tectonic forces split them apart in a phenomenon called continental rifting. Tyrone Rooney has spent his career solving the mystery of how rifting works.

The Michigan State University earth and environmental sciences professor has analyzed rocks at one of the Pangea breakup points on the Angolan margin. He’s made glass from ground-up rock found in the Great Rift Valley in East Africa and scrutinized its crystals, looking for hints at what’s causing continents to break apart today.

Rooney’s work in the College of Natural Science is fundamental, meaning his goal isn’t direct application. But the implications for his work, funded by the National Science Foundation, are endless. Future researchers could apply his research to seismic models to help them assess earthquake hazards. Oil companies, which have significant operations in offshore Angola, can better understand how sediments filled the basin formed by rifting and generated oil under the Earth’s crust.

It all starts with learning why tectonic plates break apart in the first place.

“There’s a question as to whether every plate has within it materials that tend to melt easier, like a Shakespearean character who carries the seeds of their own destruction,” Rooney said. “It’s possible the plates always have that fatal flaw. We’re trying to understand how this flaw gets activated.”

Since joining MSU’s faculty in 2007, Rooney has devoted his career to studying continental rifting. He travels wherever there’s a past or future rupture in the Earth’s crust, authoring or co-authoring nearly 70 papers as he tries to crack the code of what causes continents to rift apart. At MSU, he’s mentored more than 50 students, training up the next generation of geochemists.

Now, he’s also among the leaders of the American Geophysical Union, a global organization that supports more than half a million advocates and professionals in the Earth and space sciences. Rooney is the new president-elect of the Volcanology, Geochemistry and Petrology division.

Photo credit: Finn Gomez

Rooney said he’s relied on the American Geophysical Union, or AGU, not just for information but also for connecting with other scientists. These connections and friendships are what’s led him to new projects and ideas. The people he’s met have led to collaborations and a greater depth of research.

“It’s inconceivable to me how you could be successful as a scientist without that degree of connectivity with others,” Rooney said.

A geology convert

Like many of his geology students, Rooney was a late convert to the field. The Dublin, Ireland native was interested in studying pharmacology at University College Dublin when he took a geology class on a whim. His instructor, an igneous petrologist, taught him about more than facts in a book. He taught Rooney about wonder.

“It was a testament to his ability to communicate,” Rooney said. “He communicated the fact that things weren’t all known. The idea that there are problems we don’t know about was exciting to me.”

Hydrogeology at Penn State University brought Rooney to the United States. After studying tunnels and water inflow, he decided to return to the subject that had first intrigued him in the first place.

Looking for deep earth clues

Geochemistry is a tool to probe Earth’s processes. To understand what’s happening far below the Earth’s surface, Rooney studies basalt rocks made from solidified lava. Just as a biologist collects cell samples, Rooney collects these rocks because they’re samples of the deep earth.

“They’re direct from a part of the Earth we can’t get to,” Rooney said. “It tells us about what processes are happening. The thing is, you don’t generate melt in the earth unless something is happening, and that process is what these lavas record.”

Photo credit: Finn Gomez

Rooney looks for those clues in places where two tectonic plates have moved apart. One of his projects is at the Angolan margin in West Africa, which formed when the supercontinent Pangea ripped apart millions of years ago to form today’s seven continents.

But continental rifting isn’t a thing of the past. In East Africa, huge slabs of earth are actively pulling apart, forming what’s known as the Great Rift Valley. What looks like a beautiful valley is a rupture in the Earth’s surface. It’s a hotbed of geological activity, with volcanoes, hot springs and earthquakes. If rocks are Rooney’s samples, then the Great Rift Valley is his ideal laboratory.

The basalt rocks he collects from the deep rifts have chemical clues hidden inside them. To find these clues, he first must return the rocks to their original state – magma.

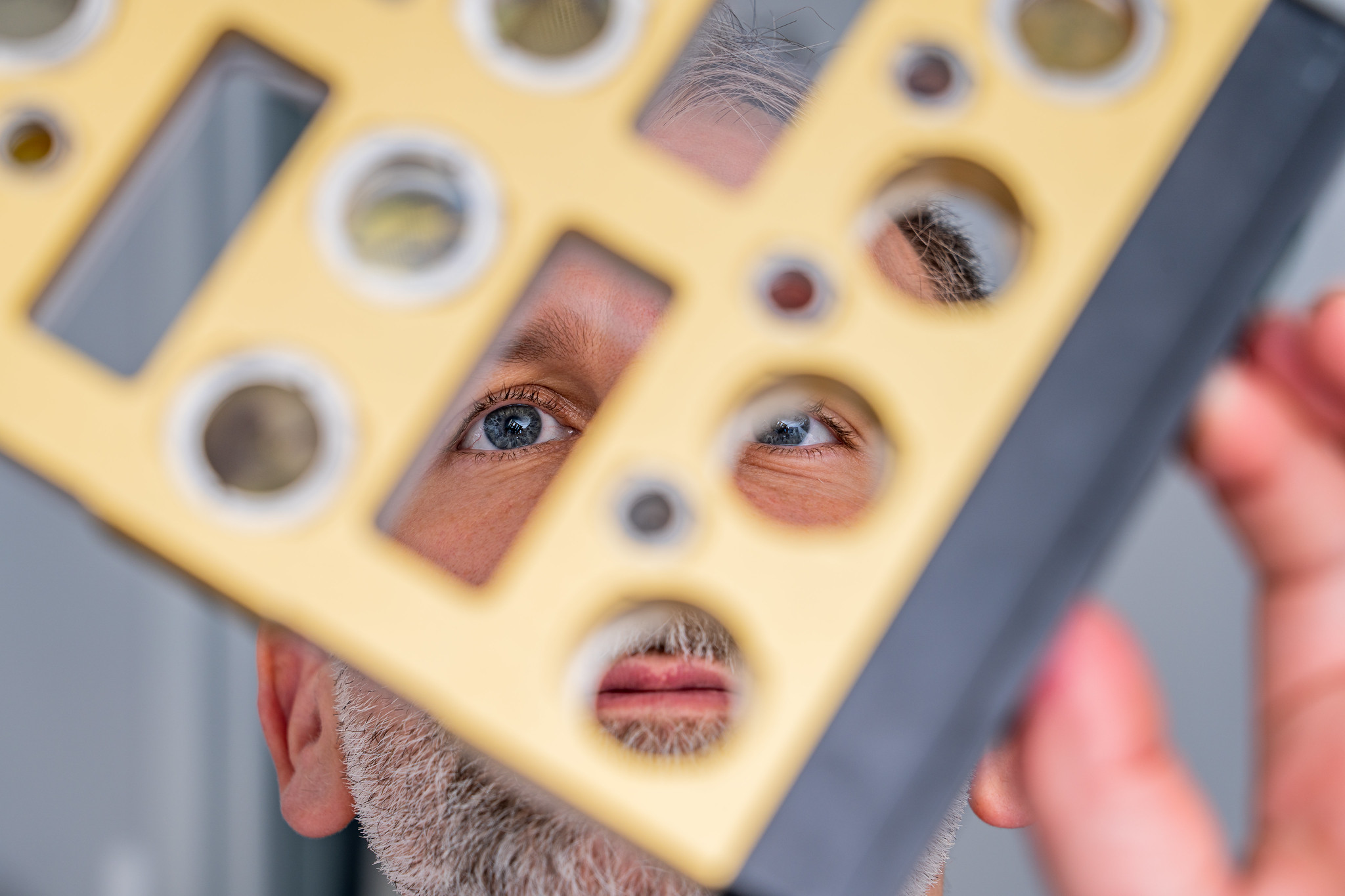

First, Rooney and his lab grind the rock into a powder and mix it with chemicals before heating it to a high temperature. Once the rock melts, it’s quickly cooled into a glass that’s perfectly homogenized. His lab uses an X-ray and then a laser system to analyze the glass’s composition.

Photo credit: Finn Gomez

Another option is to slice into the rock like a piece of cake to examine the layers. The slices are so thin they’re transparent, about the width of a hair. Crystals hiding inside the rock are visible in those slices, making their composition ripe for analysis.

The chemistry of those rocks tells Rooney the secrets hiding deep below the earth’s surface. He can decipher the depth from which the magma came, and whether it was the plate itself it melted, or something sitting above or below it. Rooney can tell the approximate temperature that created the magma, and what might have happened to the magma during its journey to the Earth’s surface.

Every bit of information offers a clue to why the plates are breaking apart. Maybe excess heat from deep in the Earth is creating the rift, or maybe giant plumes in the Earth’s mantle are sending materials under the plates that break up the surface.

“I try to understand how the Earth is functioning using the chemistry of rock, and how that tells us what’s happening at depth,” he said.

Rooney’s work has taken him to the Middle East, the Panama Canal, New Zealand, Cape Town in South Africa and even Duluth, Minn. How does Rooney find his projects? It’s all about connections. He ended up in East Africa because his Ph.D advisor had a project proposal there, and she needed a student. Rooney volunteered and has never truly left. His decades of work eventually inspired him to put pen to paper, and in 2020, he published a five-part tome on the magmatism of East Africa.

“I continued working there because I saw the different linkages that could happen,” Rooney said. “I was able to write proposals to get the funding to work on some of these things.”

Photo credit: Finn Gomez

Dedicated to discovery

Rooney’s goal isn’t flashy papers. He and his lab are dedicated to constant productivity and understanding the processes happening beneath the Earth’s surface.

Rooney is proud of his massive undergraduate research footprint, as well as his graduate students who are busy with projects of their own. He brings them to study giant basalts and mineral deposits in the Duluth Complex and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where a continental rift started in Minnesota but never made it to completion. His undergraduate students have published their own papers in peer-reviewed journals.

In his lab, Rooney and his students serve other MSU departments, turning materials into pressed powders and analyzing samples. His students learn how to run the samples themselves and operate the high-level analytical machinery.

“From the natural sciences perspective, having this machinery within the college is important because it facilitates a significant amount of research within the university,” Rooney said.

Even as Rooney continues his current projects, he’s always on the lookout for the next. He’s on sabbatical, stringing together his connections and a bit of serendipity.

His under-earth detective work continues. Wherever there’s a continental rupture, wherever there are potential clues to the mystery of Pangea, Rooney will be there.

- Categories: