Smart bombs and isotopes: how Spartans rewrite the rules of cancer care

The fight against cancer is one waged on many fronts, from the perseverance of patients and loved ones, to the tireless work of healthcare professionals.

This fight is also one of knowledge.

Our fundamental understanding of cancer expands by the hour thanks to the lifelong efforts of researchers in fields such as chemistry, physiology and genetics.

At Michigan State University alone, you’ll find over 100 scientists devoted to battling cancer every step of the way. Collectively, this research results in improved treatments and healthier lives.

That’s why on this year’s World Cancer Day, the College of Natural Science is highlighting Spartan breakthroughs that are changing the future of cancer care — how we understand, detect and beat the disease in all its forms.

Packing a radioactive punch

Being home to a top-ranked nuclear science program, it’s no surprise that MSU is rewriting what’s possible through radiotherapy — the process that delivers radioactive isotopes directly to cancer cells to damage their DNA.

With a nod to bringing local, fresh ingredients directly to our dinner plates, one team of Spartan chemists is applying their own “farm-to-table" approach in the fight against prostate cancer. From production and research to clinical testing, it’s all happening in East Lansing.

Supported by the Michigan State University Research Foundation, the team of researchers is studying a special ingredient called promethium-149, or 149Pm, which they harvest as a byproduct of experiments done at MSU’s Facility for Rare Isotope Beams.

This powerful isotope packs a higher dose of radiation than other industry standard radiotherapeutics currently used to treat prostate cancer, making researchers optimistic it can one day provide improved treatments.

“Starting with 149Pm, we’re pioneering a comprehensive strategy for developing targeted radiopharmaceutical therapies,” said professor Carolina de Aguir Ferreira, who leads the project alongside radiochemists Alyssa Gaiser and Katharina Domnanich.

“We’re excited about the potential to make a real difference in patients’ lives,” de Aguiar Ferreira added.

In the Department of Chemistry, you’ll likewise find researchers like Jinda Fan who are developing the next generation of radiopharmaceuticals needed to treat a wide variety of cancers.

This includes bismuth-based isotopes to treat melanoma and bladder cancer, as well as the materials medical specialists use to precisely image and diagnose disease.

When a patient visits their radiologist for positron emission tomography — better known as a PET scan — a radioactive tracer provides a real-time look at the body’s metabolic activity, helping pinpoint areas of concern.

At MSU, Fan and Dr. Kurt Zinn of the College of Veterinary Medicine have established an on-campus radiopharmarcy which produces a new fluorine-18 labeled radiotracer. The radiotracer is currently being used in gene therapy clinical trials at Henry Ford Health.

“This tracer allows us to visualize the successful delivery of genes to tumors in patients,” said Fan, an assistant professor who also holds appointments in the departments of Radiology and Pharmacology and Toxicology

“These doses will be produced at our MSU facility and delivered directly to the hospital for patient PET scans.”

Using ‘smart’ bomb therapy to destroy breast cancer

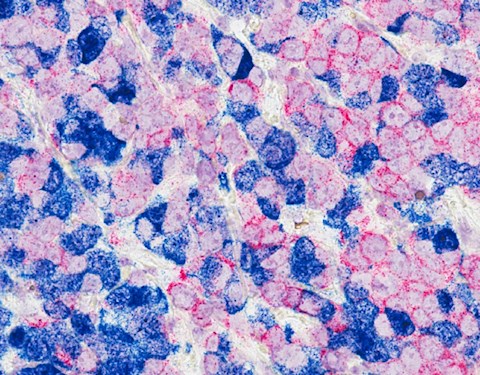

Sophia Lunt, a professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, or BMB, was recently part of a team that revealed how light-sensitive chemicals could be used to destroy metastatic breast cancer tumors in mice with few side effects.

In collaboration with husband Richard Lunt, who’s the Johansen-Crosby Endowed Professor in Chemical Engineering, as well as scientists at the University of California Riverside, the group used what’s called photodynamic therapy.

During this process, light-sensitive chemicals known as cyanine-carborane salts are introduced into the body, where they eventually accumulate inside cancer cells.

When near-infrared light penetrates the body, these salts are activated like microscopic “smart” bombs, killing the cancer cells while sparing healthy ones.

“Our innovative cyanine-carborane salts offer a targeted option with reduced side effects for patients with aggressive breast cancer,” said Sophia Lunt.

“We expect this research will lead to safer and more effective therapies for patients with limited treatment options.”

Origin stories

Where does a particular kind of cancer come from? What biological or environmental factors influence the disease?

These are the questions a scientist like Jian Hu asks when he’s unravelling the biochemistry of a group of proteins called “Zrt-/Irt-like proteins,” or ZIPs for short.

These proteins help transport important metals into our cells, but when the process goes wrong, it can lead to dangerous outcomes.

Of the 14 different types of ZIPs found in humans, there’s one in particular Hu and his group are keeping an eye on when it comes to cancer.

“We’re especially interested in ZIP4 because it’s upregulated in about half of the different types of cancer, including breast cancer, ovarian cancer and pancreatic cancer,” said Hu, a professor in BMB and Chemistry.

By studying how ZIP4 functions, Hu ultimately hopes to develop an inhibitor that will keep the protein in check.

Meanwhile, just down the hall, BMB department chair Olorunseun “Seun” Ogunwobi is exploring the molecular mechanisms of solid organ cancers and questions of cancer health disparities.

As founder of MSU's Center for Cancer Health Equity Research, Ogunwobi heads a growing research effort that’s examining the impact of cancers on underserved communities from a variety of angles.

These include molecular and genetic factors, as well as variables like pollution, diet and socioeconomic pressures. Combined, the center is leveraging MSU’s research strength to improve the cancer outcomes of vulnerable communities in Michigan and beyond.

Training the next generation of scientists

In labs and classrooms across MSU, you’ll find the future faces of cancer research hard at work — like doctoral student Sarah Marei.

It was during her undergraduate and master’s programs, both completed at the American University of Beirut in Lebanon, that Marei knew she would dedicate her scientific career to studying breast cancer.

“I've always been interested in women’s health research and cell biology,” said Marei. “I became particularly intrigued by how tumors evolve, adapt to their environment and evade immune detection, and ultimately, how we can stop it,”

During her Biomolecular Science rotations at MSU, Marei joined three labs, each focusing on aggressive forms of breast cancer.

During one of these rotations, she worked alongside BMB’s Jennifer Jacob, whose group explores the spontaneous development of tumors in mice, before eventually joining Eran Andrechek in the Department of Physiology.

In the Andrechek Lab, Marei’s currently exploring the molecular and environmental profiles that drive lymph node metastasis in breast cancer with hopes of uncovering new therapeutic targets.

“In the future, I hope to investigate how we can manipulate these pathways to prevent metastasis and improve treatment outcomes for breast cancer patients,” she added.