Zika evades early pregnancy protections, MSU research shows

Michigan State University researchers have found that the Zika virus can halt an embryo’s development in the earliest stages of pregnancy, signaling that the risks posed by the virus are greater than previously appreciated.

This is objectively bad news, but the knowledge will help people better prepare for future Zika outbreaks, researchers said. For example, doctors can work with patients who are expecting or trying to conceive children to take more robust precautions to avoid Zika’s most severe outcomes, including miscarriage and birth defects.

The team from MSU also hopes its work, which was performed with mouse models, will inspire more studies examining how other diseases, such as cytomegalovirus — the leading infectious cause of birth defects — affect early pregnancy.

“Hopefully, this can be a push to look at what other viruses and bacteria could be causing embryo demise, specifically in these early stages,” said Jennifer Watts, the first author of the new study published July 28 in the journal Development.

“These are really critical windows of development,” said Watts, who worked on the study as a doctoral student in Amy Ralston’s laboratory in the College of Natural Science. Watts is now a postdoctoral scientist at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Ohio.

The findings could also spur the development of an approved and effective Zika vaccine, which currently does not exist, Ralston said. Especially if there is another epidemic similar to the one experienced by the U.S., Brazil and other countries in the Americas in 2015 and 2016.

“It’s feasible that there could be a Zika vaccine if people realized the full spectrum of threats this virus has, or that a vaccine could be pushed faster,” said Ralston, the James K. Billman, Jr., M.D. Endowed Professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

‘Nobody was talking about it’

In showing that the virus can directly affect an embryo’s cells early in development, the research is also underscoring the dangers of Zika as a sexually transmitted pathogen.

“When we were traveling and going to conferences in 2015 and 2016, we’d see banners and signs warning about mosquito transmission,” Watts said.

“People knew it was sexually transmitted, too,” Ralston said. “But nobody was talking about it."

This is especially important because expectant parents and their unborn children are the populations most vulnerable to Zika. For the average person, Zika’s symptoms are usually mild if they’re noticed at all. But more than 3,700 babies were born with birth defects attributed to Zika during the 2015-16 epidemic in North and South America. The birth defects included microcephaly, a condition in which a child’s head is much smaller than expected.

Pregnant people also faced an increased risk of preterm births and miscarriage. Now, the MSU research, which was supported by the National Institutes of Health, is showing that Zika can stop an embryo’s development within the first week of conception, before a fertilized egg implants in the uterus.

“People wouldn’t even know they’re pregnant within that week,” Watts said. “That means the virus could be a cause for infertility for people who are trying to conceive but not having success.”

Statistically speaking, Zika’s worst consequences are uncommon. Birth defects, for example, were found to occur in about one in 20 possible cases in the U.S. But the potential severity and the range of outcomes drew Ralston and Watts to the problem.

“Why do you have birth defects in some babies but not others?” Ralston said. “It’s something we still don’t know and it’s obviously worth studying.”

It was a different type of research project for Ralston’s team, which usually studies the fundamental biology of healthy early embryo development. But she and Watts knew they had the expertise and support at MSU to help answer how Zika viruses present at conception could affect the course of a pregnancy.

“I remember thinking, ‘Why hasn’t anyone checked?’” Ralston said. “Then I thought, ‘Well, who would do that? I guess we would.’”

Watts was a key ingredient in that “we.” Although Ralston’s team had the biological know-how and microscopy skills to probe that question, there was a huge virology component that Watts took on learning as a graduate student.

“There were times, as her graduate adviser, I couldn’t actually advise her,” Ralston said. “I’m not a virologist, but Jenn had the perfect personality for this project. She would just go out and find the answers.”

‘It wasn’t what we wanted’

To that end, Watts worked closely with the lab of Zhiyong Xi a professor in the Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics. Xi studies mosquito-borne illnesses and, in 2017, he led one of the 21 grants awarded by the U.S. Agency for International Development’s $30 million Combating Zika and Future Threats program.

With help from Xi’s lab, Watts learned the skills she needed to design experiments, then measure and analyze the effects of Zika virus on developing mouse embryos.

Meanwhile, other researchers were racing to answer similar questions. For instance, during the MSU study, other scientists showed that Zika could alter the course of normal placenta development. But questions remained about Zika’s direct effects on the embryo, especially because it has a thick protein coat called the zona pellucida.

The coat protects the embryo during early development, but researchers already knew it wasn’t completely impenetrable. Studying whether the zona pellucida held up against Zika would provide key insights into the complete spectrum of ways the virus could affect pregnancies.

Watts, Ralston and their colleagues had the breadth of expertise to examine how Zika influenced different cell types at different times during early embryonic development, providing that more complete picture. Unfortunately, the team found that Zika eluded the shield.

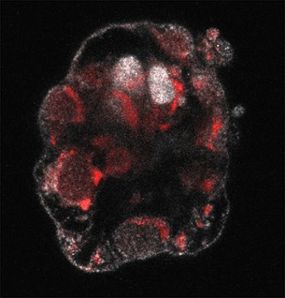

“It wasn’t what we wanted to happen,” Watts said. “We could see the development arresting at a certain stage. For example, we’d see a fertilized egg infected when it was in its two-cell stage and it wouldn’t grow past eight cells or the blastocyst stage. That’s devastating.”

The next step, though, is turning that devastating news into something positive. To do that, the MSU researchers are sharing their work and providing valuable new information to the research and public health communities. That way, the next time Zika appears — which experts say is a matter of when and not if — they can offer valuable advice and collect important data they weren’t thinking about seven years ago.

“We can really inform epidemiologists what to look for and what to think about when they see differences in pregnancy outcomes,” Watts said.

“They know how to look for it,” Ralston said. “But they aren’t going to look for it unless they know they should.”

Banner image: Spartan researchers reveal a more complete picture of how sexual transmission of the Zika virus affects early embryo development. Credit: Watts, J., Ralston, A. Development. 2022