Plants in space: Seeding a sustainable future

The moon holds answers, and a Michigan State University plant biologist and her team is bringing those answers within reach. Patience, creativity and a cheerful fearlessness are turning insights buried in plant seeds into pathways to the very survival of the human race.

“Look at the moon,” plant biologist Federica Brandizzi said from her MSU laboratory. “It’s a spot in the sky and now I know it’s something we can grab.”

She said this just days after taking a special delivery from NASA—cardboard boxes

cradling seeds fresh off a space trip that stretches the concept of being “out in

the field.” MSU sent those seeds on the Artemis I mission, Nov. 16, for a 25-day,

mind-blowing 1.4-million-mile ride. They were returned to the Brandizzi lab on Jan.

5.

This is the third time Brandizzi’s team has put plants in space.

The seeds of the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (A. thaliana) flew farther than any spacecraft built for human transport has ever flown. They looped 40,000 miles through two giant donuts of radiation around Earth called the Van Allen Belts and traveled beyond the far side of the moon. The seeds were subjected to unknown conditions of gravity, vibration, radiation and temperature that were literally out of this world.

The seeds on the unmanned Orion spacecraft rode with other experiments that will help address important questions that humanity needs to answer as spacefaring missions carrying people become longer and more ambitious. Brandizzi’s team stake in that long game: How will that long-term human presence feed itself?

“The short answer is that space travelers will need to grow their own food,” said Brandizzi, an MSU Foundation Professor in the College of Natural Science and the MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory. “There are no grocery stores on the moon (yet) and launching care packages of food to astronauts simply isn’t sustainable.”

She is also deeply invested in another long game. Feeding human exploration of space is a step toward facing the urgent reality that creating human-sustaining real estate on a changing planet is necessary.

“Our resources on Earth are limited,” she said. “We need new space because Earth is limiting. I have three children, and it makes me realize we must make sure there is a future for them.”

Plants grow differently in space than they do on Earth. So, over the past few decades, scientists have been working to better understand plant biology and determine what it will take to allow plants to survive and maybe even grow better on another planet.

From previous experiments, scientists have learned that space can reduce the levels of protein building blocks, or amino acids, that keep living organisms—including plants—strong on Earth. The same amino acids would also be nutritious for people who eat the plants.

Brandizzi’s lab selected seeds enriched with those amino acids, making them not only potentially more fit for space travel, but also more nutritious. They were packed up along with regular seeds for comparison. This experiment will allow the MSU team to see if fortifying the seeds on Earth could create a more sustainable path to growing healthier plants—and food—in space.

The team’s experiment is one of four selected by NASA’s Space Biology Program to better understand how deep space affects terrestrial biology. Accompanying MSU’s seedlings aboard Artemis’s Orion spacecraft were a yeast experiment led by the University of Colorado-Boulder, a fungus experiment led by the Naval Research Laboratory and an experiment with photosynthetic algae led by the Institute for Medical Research, a nonprofit research corporation.

“In space, there are so many variables, so many things that plants have never experienced before,” Brandizzi said. “For example, without Earth’s gravitational pull, plants are weightless in space. And without Earth’s shielding atmosphere, plants encounter higher doses of cosmic rays.”

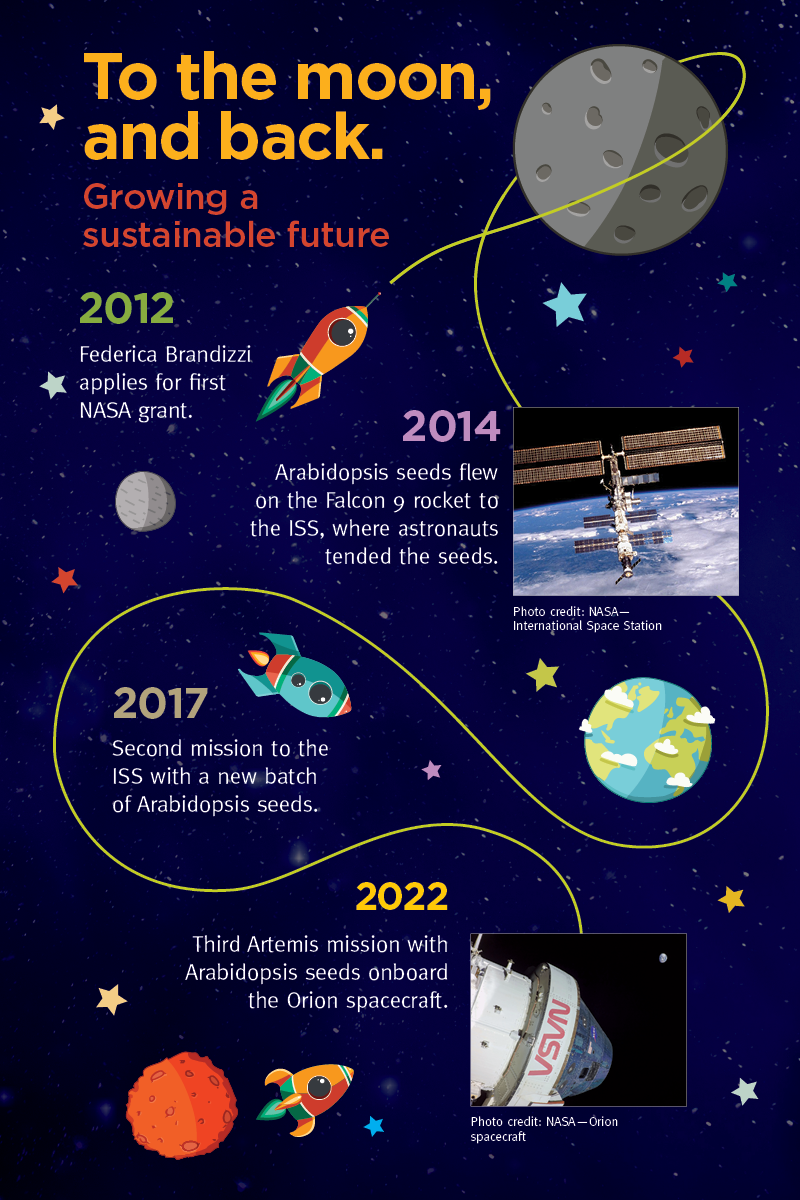

A decade of plants in space

In 2012, Brandizzi applied for a NASA grant to understand the mechanisms of how plants coped with the unique stress plants would undergo when taken from their home planet. The grant application said, “to facilitate plant life in space, it is crucial to acquire a better understanding of the genetic changes that enable plant cells to respond to spaceflight stress.”

Her group already had identified a protein that regulated stress responses and argued they’d need to put plants with a well understood genome—Arabidopsis—in what they called a hostile environment to get a better idea of how that protein worked. Understanding how plants respond to that kind of stress opens doors to developing plants better equipped to cope in a new world. There also was a proposed bonus development: understanding and helping plants with space stress management could also design coping mechanisms for what scientists call “other multicellular organisms”—humans.

The maiden voyage for her work included lessons that went far beyond the innerworkings of the plants. Packing for travel in space is about supreme efficiency on all levels—how much room an experiment can take up, how finite resources are, and how low gravity effects the simplest tasks. For instance, even watering plants demands creativity, since water won’t fall, but instead float around and clump into buoyant blobs.

Then, in April 2014, the group loaded Arabidopsis seeds edited to override defects in anticipated stress responses, along with standard seeds. They were stacked compactly into sleeves called BRIC-PDFUs—Biology Research In Cannisters-Petri Dish Fixation Units—and loaded onto NASA’s Falcon 9 craft bound for the International Space Station.

The International Space Station astronauts tended the seeds, which ultimately sprouted into skinny, stressed-out plants. With little gravity and light to control them, Arabidopsis grew out of their evolutionary comfort zone, their stems and roots sprawled in all directions.

These sprouts returned to Brandizzi’s lab so the team could begin to understand the genetic changes that informed what plants needed to grow properly in space.

In 2015, she submitted and received another NASA grant to again put another experiment up to build on those findings, tweaking mutant plants’ stress responses. This led to the second plants-in-space experience being in orbit via the SpaceX CRS12 mission to the ISS in August 2017.

In 2018, she applied for space on the Artemis I flight. It was time, they submitted, for Arabidopsis to face new stresses to answer new questions. Their project was selected and MSU’s seeds flew on the Artemis I space mission last November.

The well-traveled seeds arrived back in East Lansing, Mich., in January, and the team is now analyzing the seeds.

Joanne Thompson, a Ph.D. student in Brandizzi's lab, played a key role in the lab's seed experiment with NASA. She was responsible for analyzing the seeds. Some went into -80 degree storage for future work.

The trick, she said, is to use as few seeds as possible when working to understand how the amino acids may have changed.

"The experiments were planned in advance so we know the minimum amount of seeds we would need. Thinking ahead, we included more seeds than required for possible experiments in the future," she said. "That's the greatest things about Arabidopsis--the sheer volumen of science we're able to get back with these tiny seeds."

To ensure results can be replicated, some of the seeds stayed at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, with the conditions carefully coordinated to be the same in both spots.

Working with NASA on these experiments has been a dream come true and an incredible opportunity to introduce her team to a different way of conducting research, Brandizzi said. Unlike her team’s more conventional projects, the team can’t adjust on the fly or make changes to the experiment after it launches, in this case literally.

“You only get one shot, so everything has to be perfect,” she said. “The preparation is intense, it’s tiring, but it is so rewarding.”

Banner image: The moon holds answers, and Michigan State University plant biologist Federica Brandizzi and her team is bringing thos answers within reach. Patience, creativity and a cheerful fearlessness are turning insights buried in plant seeds into pathways to the very survival of the human race.