Getting to the root of visceral pain

Article Highlights

- Researchers at Michigan State University have shown that cells known as glia could lower the threshold to trigger visceral pain in patients, such as those with irritable bowel syndrome, who have experienced inflammation in the gut.

- The team discovered this phenomenon in mice, meaning the results may not completely extrapolate to humans.

- Still, the work provides a new avenue of exploration to better treat visceral pain, which is the most common gastrointestinal issue.

Researchers at Michigan State University may have discovered why visceral pain is so common in people who have experienced inflammation in their guts, including patients with irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS.

Working with mouse models, MSU physiologists showed that nervous system cells known as glia can sensitize nearby neurons, causing them to send pain signals more easily than they did prior to inflammation.

“The glia drop the threshold for activating a neuron,” said MSU Research Foundation Professor Brian Gulbransen, whose research team authored the new report in the journal Science Signaling.

“So, something that wasn’t painful is now painful,” Gulbransen said. “It’s like when you put on a shirt after getting a sunburn.”

This discovery could help researchers develop therapies to lessen or eliminate visceral pain by counteracting the glia’s sensitizing efforts.

Currently, no medicines on the market are designed to act directly on glia, but pharmaceutical companies are investigating that approach, Gulbransen said.

The team’s work offers new information that could help tap into that potential, but it also comes with an important caveat.

The team didn’t exactly measure pain. Rather, what they observed was connected to something called nociception.

Nociception is essentially the signals the nervous system sends in response to physical stimulus. Pain is related but also includes how our brains interpret those signals.

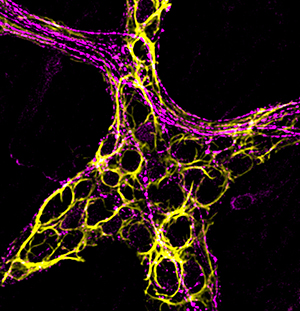

Michigan State University research on the causes of visceral pain in the gut was featured on the cover of November 21 issue of the journal Science Signaling. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

“In general, nociception is pain, but you can have one without the other,” said Gulbransen, who works in the Department of Physiology. “It’s a little bit of a funny distinction between the two, but it becomes important when extrapolating results from animals to people.”

Still, Gulbransen is excited by his team’s finding.

“The major thing here is that it suggests a new mechanism contributing to pain in the gut,” he said. “And visceral pain is the most common gastrointestinal issue.”

Listening to ‘silent’ cells

The enteric nervous system, the part of the nervous system running through our gastrointestinal tract, is an important but often overlooked part of our anatomy. In fact, it’s been nicknamed our second brain.

So perhaps it’s not surprising that “important but often overlooked” also aptly describes glial cells in the gut.

Unlike neurons, glia are not electrically active. As researchers developed and refined techniques to probe neurons, the same methods weren’t effective for investigating glia.

“If you tried to record electrical signals from glia, it was just noise. Nothing interesting happened,” Gulbransen said. “Glia were sort of ignored as these silent, passive cells.”

It turns out, however, that glia are very active chemically. That is, they react to many different compounds in the body, and they can release different biochemicals in response.

With the advent of new analytical tools and techniques, researchers have become better equipped to observe these cells. Gulbransen’s team took advantage of advances in genetic and chemical techniques to monitor glial cells before and after inflammation in the gut.

“Normal glia in a healthy gut do not change nerve fiber sensitivity,” Gulbransen said. “But inflammation triggers a change.”

The team discovered that, when exposed to inflammation, glia began releasing compounds that altered the chemistry of the gut and sensitized nerve fibers.

The investigation was spearheaded by Wilmarie Morales-Soto, who earned her doctorate working on this project in Gulbransen’s laboratory. She’s now a postdoctoral research fellow at the Mayo Clinic.

The research team also included research associate Jacques Gonzales and William Jackson, a professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology.

Moving forward, Gulbransen and his team are eager to explore looming questions related to visceral pain.

For example, data show that females are more likely to experience visceral pain than males. Early life adversity, including stress and trauma, can also make people more susceptible to visceral pain.

Glia are implicated in both situations and learning more about them could help innovate new ways to treat gut pain.Banner image: Although glial cells, like the ones visible in green in this micrograph, aren’t electrically active, they are chemically active. After inflammation in the gut, glia release a compound labeled with green that can sensitize neurons. Reprinted with permission from Morales-Soto, W. et al., Science Signaling, 16:eadg1668 (2023)