How the soil microbiome recovers after environmental calamity

Article Highlights

- By analyzing both DNA and RNA from soil microbes near the Centralia mine fire, Michigan State University researchers have discovered new information about how nature responds to and potentially recovers from unnatural disasters.

- Published in the journal Ecology Letters, the research could provide insights to help restore soil health in the face of other environmental disturbances caused by humans, including climate change.

- “Many people don’t realize that an incredible number of soil microbes are simply not active and functioning at any given time. This is an important point because the active microbes are the ones that contribute to ecosystem functions,” said Ashley Shade, the principal investigator of the new report. “I think this is special about this study because most research does not consider this question of who’s active and who’s not.”

Microbes are vital to maintaining healthy, fertile soil, which, in turn, is vital to the overall health of ecosystems. But what happens to these microbes when humans cause long-term damage to the environment?

Michigan State University researchers have provided new answers to that question by analyzing soil microbes near a mine fire that’s been burning for more than 60 years.

“If you look in a gram of soil, you have tens of thousands of different bacterial species in that soil,” explained Ashley Shade, the principal investigator of the report documenting the new insights published in the journal Ecology Letters.

Ashley Shade led a new research report in the journal Ecology Letters. Credit: Yann Dufour

Shade is an adjunct associate professor in MSU’s Department of Microbiology, Genetics and Immunology.

“Soil is the most diverse microbiome that we know,” Shade continued. “It’s more diverse even than the human gut.”

For seven years, Shade and Samuel Barnett, a postdoctoral scholar in her lab, have been studying soil microbial communities in Centralia, Pennsylvania. The town is the site of an underground coal mine fire that has been burning since 1962.

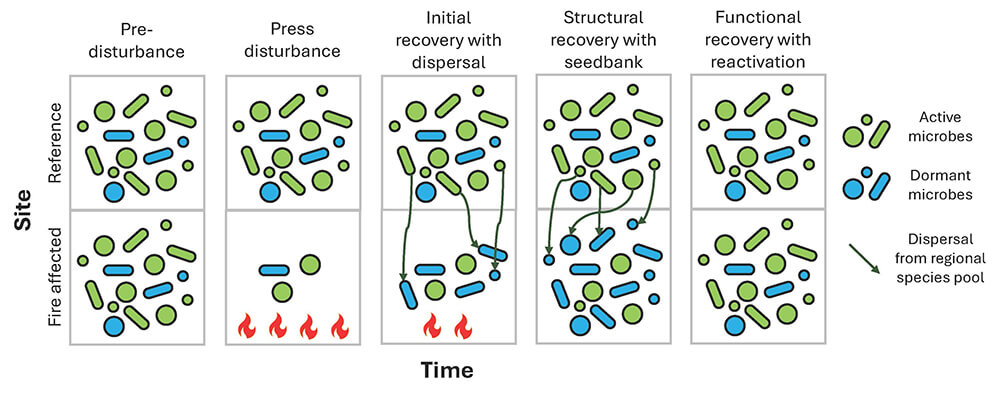

The Centralia mine fire is an example of a “press disturbance” — a long-term, continuous, human-caused disturbance.

In this study, the researchers used this system as a model to try to understand how bacterial communities respond and potentially recover in the face of an intense environmental change. This is particularly important in the face of another press disturbance: climate change.

In fact, the team hopes that its findings will spur additional research into the development of strategies for microbiome restoration for ecosystems impacted by climate change and other press disturbances.

A tale of fire and microbes

The Centralia fire started accidentally when efforts to clean a landfill ignited the adjacent mine, and it has been burning continuously since then. As the fire burns, it moves through the abandoned underground mine shaft, heating the soil above it as it travels. This heat changes the structure of the microbial communities.

With support from the National Science Foundation, the researchers selected sampling sites at different points along the fire’s path and examined the soil before, during and after being heated. The team also sampled from nearby sites that are completely unaffected by the fire.

Marco Mechan-Llontop (left) and Samuel Barnett (right) work at a sampling site near the Centralia mine fire in October 2021, when they were both postdoctoral scholars in the Shade lab. Credit: Keara Grady

The sampling was conducted yearly between 2015 and 2021.

“We go out every October and we take soil cores,” Barnett explained. “We have a big PVC pipe that we sterilize and drive into the soil and pull out about 20 centimeters or 8 inches of soil. Then we sieve the soil to get rid of roots and rocks and the stuff we don’t want and then freeze it in liquid nitrogen and bring it to the lab.”

The next step was for the researchers to extract bacterial DNA and RNA. They sequenced the DNA to determine which types of bacteria are present. They then looked at the ratio of RNA to DNA to determine which bacteria are biologically active and which are dormant.

“Dormant is a word for a reversible state of activity that many life forms assume at some point. It’s a really important strategy to help organisms withstand stress in their environment,” Shade said.

“Many people don’t realize that an incredible number of soil microbes are simply not active and functioning at any given time. This is an important point because the active microbes are the ones that contribute to ecosystem functions,” she continued. “I think this is special about this study because most research does not consider this question of who’s active and who’s not.”

The researchers infused this perspective into the recovery of microbial communities.

Although the microbial populations recovered after the fire had passed — with new bacteria being blown in by wind, for example — the species that were active or dormant had changed compared with conditions before the fire.

“If we can understand what wakes up the dormant microbes, we can try to manage the microbiome, for example, to wake up when we need it to wake up, to go to sleep potentially when we need it to go to sleep,” Shade concluded.