Where did cosmic rays come from? MSU astrophysicists are closer to finding out

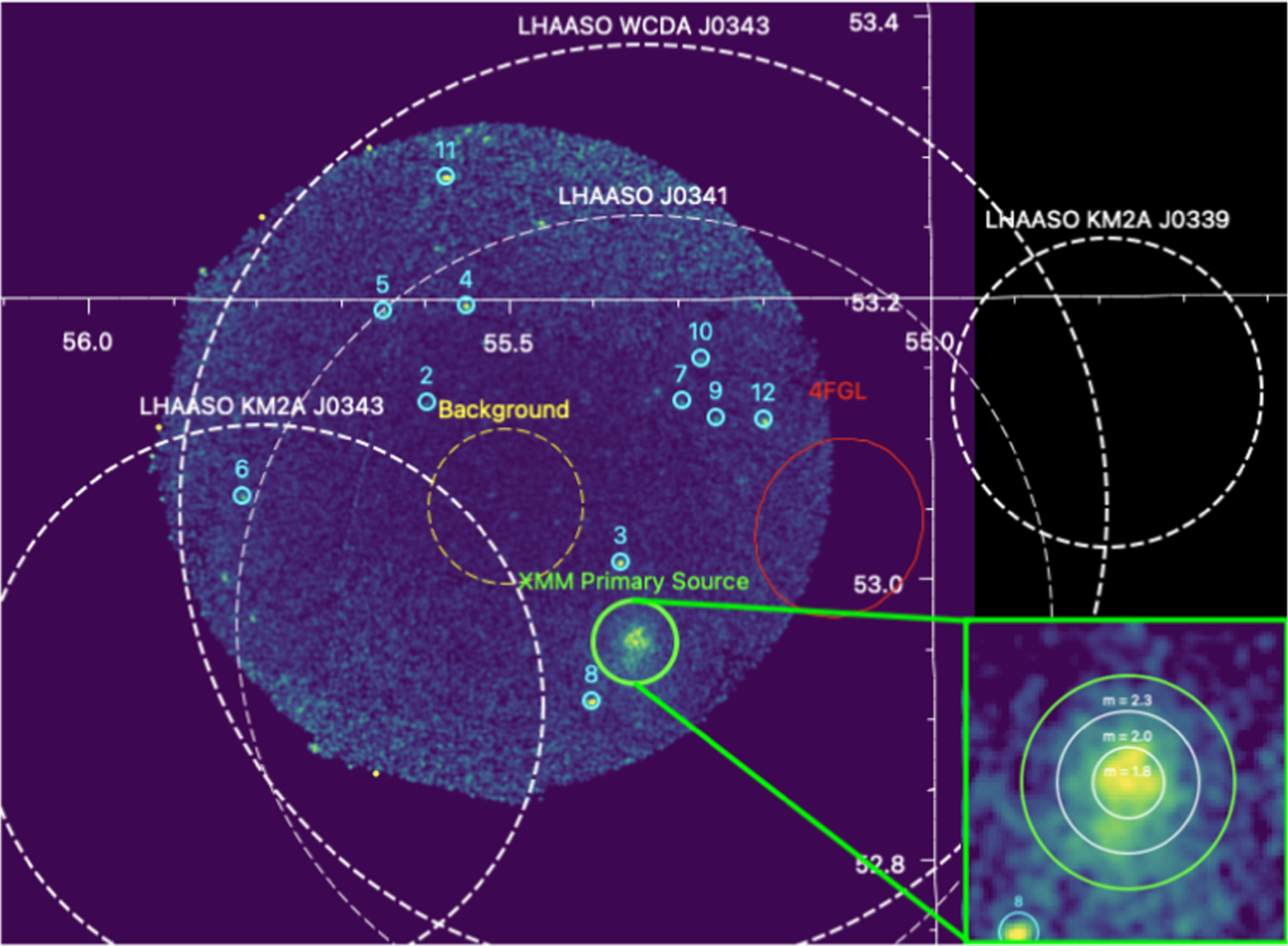

X-ray image of the newly discovered pulsar wind nebular associated with an extreme Galactic cosmic ray source 1LHAASO J0343+5254u, obtained by the XMM-Newton space telescope (DiKerby, Zhang, et al., ApJ, 983, 21)

New research published by Michigan State University astrophysicists could help scientists answer a century-old question: where did galactic cosmic rays come from?

Cosmic rays – high-energy particles moving close to the speed of light – originated from somewhere in the Milky Way galaxy and beyond, but exactly where has been a mystery since they were discovered in 1912. Shuo Zhang, MSU assistant professor of physics and astronomy, and her group led two studies that shed new light on where cosmic rays might have come from. The recently published findings were presented this week at the 246th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Anchorage, Alaska.

The sources of these high-energy, fast-moving particles could bear the nature of black holes, supernova remnants and star forming regions. These extreme astrophysical events are also known to produce neutrinos – tiny, nearly massless particles that are found in abundance not only deep in space, but also on our planet.

“Cosmic rays are a lot more relevant to life on Earth than you might think,” Zhang said. “About 100 trillion cosmic neutrinos from far, far away sources like black holes pass through your body every second. Don’t you want to know where they came from?”

Cosmic ray sources are so powerful that they can accelerate a proton or electron into energies far beyond what humans are able to do with the most advanced particle accelerator. Zhang’s group is studying these cosmic particle accelerators, known as PeVatrons, to find out where and what they are, and how they’re able to accelerate small particles into extremely high energies. Understanding more about them can help unlock fundamental questions in physics, such as galaxy evolution and the nature of dark matter.

Her group’s latest papers explore multi-wavelength studies of PeVatron candidates whose sources remained unknown. In the first paper, Stephen DiKerby, a postdoctoral student in Zhang’s group, investigated a mysterious PeVatron candidate discovered by the Large High Altitude Air Shower Observatory (LHAASO), but the nature of the source was still unknown. Using X-ray data from the XMM-Newton space telescope, DiKerby found a pulsar wind nebula – an expanding bubble with relativistic electrons and positions with energy injection from a pulsar. This finding established this PeVatron as a pulsar wind nebula type of cosmic ray source and is one of a few cases where scientists can identify the nature of PeVatrons.

In the second paper, three MSU undergraduate students in Zhang’s group – Ella Were, Amiri Walker and Shaan Karim – used NASA’s Swift X-ray telescope to observe X-ray emissions from little-explored LHAASO cosmic ray sources. The team calculated the upper limits for the X-ray emission, and their work could serve as a pathfinder for future studies.

“Through identifying and classifying cosmic ray sources, our effort can hopefully provide a comprehensive catalogue of cosmic ray sources with classification,” Zhang said. “That could serve as a legacy for future neutrino observatory and traditional telescopes to perform more in-depth study in particle acceleration mechanisms.”

Next, Zhang’s team plans to tackle another study on cosmic ray sources by combining data it collects from the IceCube Neutrino Observatory with those from X-ray and gamma-ray telescopes. They want to explore why some cosmic ray sources emit neutrinos but not others, as well as where and how the neutrinos are produced.

“This work will call for collaboration between particle physicists and astronomers,” Zhang said. “It’s an ideal project for the MSU high-energy physics group.”

This work is supported by multiple NASA observation grants and the National Science Foundation IceCube analysis grant.

- Categories: