NSF award SEEDs opportunities for Spartans

A new grant from the National Science Foundation is bringing Spartan teachers, researchers,

and students together to solve a global grassland mystery.

The award — a $1.1 million CAREER grant — is spearheaded by Lauren Sullivan, an assistant professor in the department of Plant Biology and at the W.K. Kellogg Biological Station.

Sullivan, who also serves as the Associate Director of MSU’s Ecology, Evolution & Behavior Program, envisions the project as an opportunity to transform a longstanding question in

community ecology into a training opportunity for future STEM researchers and educators.

Rain in the forecast

For years, Sullivan has worked with international collaborators to study grasslands through the DRAGNet (Disturbance and Resources Across Global Grasslands) program. Now, she's connecting Michigan State University students with an international research cohort to help students build their skills as scientists.

It’s a chance for students to make a real impact, helping scientists understand how plant biodiversity is maintained in some of the world’s most vulnerable ecosystems.

It starts with MSU students in the General Ecology class, who will collect data on grassland seeds from all over the globe under Sullivan's guidance.

“Grasslands remain the most endangered ecosystem globally due to land-use conversion to agriculture and development,” Sullivan said. “It is critical that we understand how seeds structure these systems in order to maintain our rapidly declining biodiversity."

Studying seeds presents a complex problem; for one, the seeds that fall in grasslands

are often small, ranging in size from a few millimeters long to microscopic. They

enter the environment in various ways — a phenomenon called seed rain, whether they’re

carried in by wind, water or animals.

And to top it all off, variations in physical features mean that different seeds are

spread across the landscape in different patterns and in varying quantities. This

connection between seed characteristics and dispersal is the question at the core

of Sullivan's project.

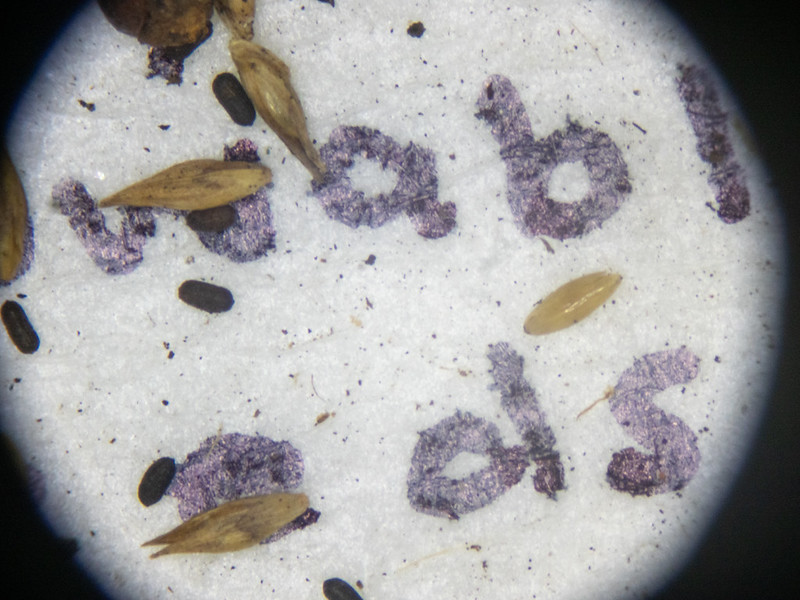

Grassland seeds, like those pictured here, come in a fascinating array of shapes and sizes. These physical characteristics are expected to hold answers to how grassland communities are structured. Credit: Katherine Wynne

This complexity has made it challenging for researchers to determine how seed characteristics shape grasslands from the plains of Montana to the vast prairies of India. But Sullivan hopes that a team of students can turn shipments of seeds into a powerful tool for scientists to better understand the characteristics of seeds they encounter in the field.

“Researchers in different countries will send us their seeds, and the undergraduates in my class will help collect data on seed traits—like their shape and size—which will then be used to answer important questions about how far seeds move in grasslands.”

This arrangement gives fledgling researchers an opportunity to develop their research skills: students who collect and analyze real ecological data through this project will practice thinking like scientists.

As far as how the students will chip in, Sullivan explained: “they will use photos of the collected seeds to measure characteristics related to movement, including shape, size and ornamentation, all which allow seeds to move longer or shorter distances.”

“They will then develop scientific research questions about what makes seeds good movers and how that relates to the plants that are in the area.”

In turn, student researchers’ observations and records will be fed into a global database and used by grassland scientists to better understand how seed qualities like shape and size are linked to seed dispersal.

Starting small, starting early

Sullivan also hopes to connect researchers, fledgling scientists, and even K-12 educators to bring hands-on ecology research to classrooms across Michigan.

To do this, she is teaming up with K-12 teachers and MSU pre-service teachers to build lesson plans that incorporate this

grassland research. Integrating these projects into pre-college classrooms brings “cutting-edge

science to middle and high school students,” Sullivan explained, and helps the involved

classrooms meet next generation science standards.

She’ll blend the work of this CAREER award with existing projects at MSU, funded by

a CIRCLE (Center for Interdisciplinary Research, Collaboration, Learning, and Engagement)

grant, to equip Michigan educators with resources to teach young students about ecology,

outdoors in their own communities.

Solving a grassland mystery

Ultimately, better understanding seed distribution may scientists understand how grasslands maintain their biodiversity: a key insight when it comes to preserving and supporting threatened grasslands across the globe.

Limitations in both observational and experimental studies have forced ecologists to make certain assumptions about how seed dispersal impacts the makeup of plant communities compared, in relation to other environmental factors. Such assumptions, Sullivan argues, create a need to investigate the impact of seed dispersal in maintaining biodiversity.

“Grasslands have some of the highest seed rain density of any ecosystem,” Sullivan

said.

“Most plant ecology focuses on the plants that are already there in the system, and

much less on how these new recruits arrive to an area and what impact they have.”

Now, Sullivan – and dozens of young scientists – can begin by taking a look at the

big impact of tiny seeds under the microscope.

About CAREER grants

CAREER grants are awarded by the NSF to early career faculty members who have demonstrated high research potential, dedication to integrating their research with student education, and interest in serving as role models in research and education.

- Categories: