In the quest for clean energy, Spartans say: go green, go light

On this year’s International Day of Clean Energy, Michigan State scientists are working around the clock to change the ways we power our world.

Thanks to breakthroughs in chemistry, bioengineering and materials science, clean energy is becoming more efficient, affordable and available for wider use.

Combined, this “green and light” combo is helping pave the way for a renewable future that makes the most of our planet’s near-limitless energy potential.

Here comes the sun

Last year was the first time on record that sustainable energies such as wind and solar created more power than coal. With demand for electricity rising – pressured by data centers, electric vehicles and other expanding industries – the race is on to improve these green technologies to keep pace.

When it comes to improving solar power, James. K McCusker will tell you that the challenge, and solution, is in the materials.

“When I give talks about energy science at undergraduate schools or to the public, I half-jokingly say that there are a lot of leaves on trees for a reason,” said McCusker, who’s the Joseph Zichis Chair of Chemistry in MSU’s Department of Chemistry

“Light capture is a material-intensive problem because of the relatively low density of energy from sunlight. Nature solves this problem by producing a lot of leaves.”

Today, most solar power, like the solar car ports and picnic tables scattered across MSU's campus, makes use of heavy elements that efficiently convert light into energy. This efficiency, however, comes at a cost.

“Elements like ruthenium, osmium, or iridium — these are some of the leastabundant in the earth’s crust,” explained McCusker.

To overcome this hurdle, his lab uses ultrafast lasers to explore the photochemical properties of elements like iron and cobalt.

If these easy-to-find elements could be integrated into solar energy conversion and storage, it would help renewable energy technologies be adopted far more widely and cheaply.

“When we move to the first transition series and elements such as iron or cobalt, availability becomes a non-issue,” McCusker said.

Taking notes from nature

While some researchers look to the sun, others are tapping into the world of plants and microbes to fuel a greener future. Such scientists are learning new tricks from nature’s stunning biochemical bounty.

Erich Grotewold, for instance, has been helping crack the genetic mysteries of a plant called Camelina sativa.

Cultivated for millennia as an oilseed crop, this plant has garnered renewed interest as a source of aviation biofuel thanks to its unique chemical qualities.

“Biodiesel from camelina won’t freeze at 30,000 feet,” Grotewold said, who's an MSU Research Foundation Professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and BMB.

“We might have electric and hydrogen-powered cars, but we’re not going to have electric or hydrogen planes anytime soon.”

Meanwhile, in Bjoern Hamberger’s lab, you’ll find research exploring the ways we might turn trees into lucrative “biofactories.”

During current biofuel production, fast-growing trees like poplars are harvested for their biomass. To make growing these trees more economically attractive, Hamberger’s team engineered them to produce additional, high-value chemicals that might also be sold.

Such chemicals can be used in cosmetics, vaccines and even perfumes.

“Biofuels are still not competitive against the cheap petrochemistry that’s out there,” said Hamberger, a James K. Billman Endowed Professor in BMB.

"If you want to sell a green product to a customer, it can’t only be green, it needs to be affordable.”

On the topic bioengineering, MSU further leads the way by being part of the Center for Catalysis in Biomimetic Confinement.

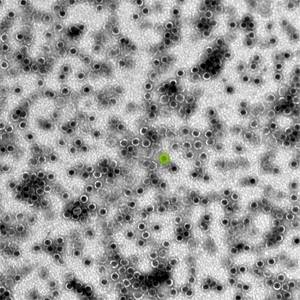

A federally-funded Energy Frontier Research Center, the CCBC brings together experts from MSU, Berkeley National Laboratory and Argonne National Laboratory to study what are known as bacterial microcompartments.

These tiny structures house powerful biochemical reactions, and with the right scientific tinkering, could be transformed into tailor-made “nanofactories” that produce molecules needed for fertilizer, clean fuels, and much more.

“Over evolutionary time, bacteria have taken these shells and put in new enzymes to repurpose the chamber,” Danny Ducat said, a professor in BMB and CCBC researcher.

“We’re following on nature’s design principles and asking, ‘How can we put what we want in there?’”

To learn more about how MSU is shaping a greener tomorrow, you can explore its sustainability mission here.

- Categories: