MSU researcher awarded NIH grant to study how unknown genes contribute to cholera pandemics

Uncovering the genetics behind a six-decade long cholera pandemic is being funded with a $2.8 million National Institutes of Health grant awarded to a Michigan State University researcher leading the study.

Chris Waters, MSU professor of microbiology and molecular genetics,and the grant's lead PI, said the research into 36 genes key to the persistence of cholera aims to increase understanding of how bacterial pandemics surface and to boost development of new viral therapies to treat bacterial infections.

Cholera is a waterborne disease that lives in the environment and infects humans. This disease kills about 100,000 people each year and can be found throughout the world with recent outbreaks in Haiti, Yemen and Ethiopia. A novel cholera pandemic emerged in 1961 and continues today.

“We want to figure out why a new cholera pandemic remerged and how it has persisted for the past 60 years,” said Waters, who holds joint appointments in the College of Natural Science and the College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Waters and longtime collaborator Matthew Neiditch, associate professor in the Department of Microbiology, Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics at Rutgers and co-investigator on the grant, sought to understand how the three dozen genes of unknown function acquired by the current cholerae pandemic strain contribute to its emergence and persistence.

“These genes had never been seen in cholera before,” Waters said. “Up until recently, we didn’t know anything about them.”

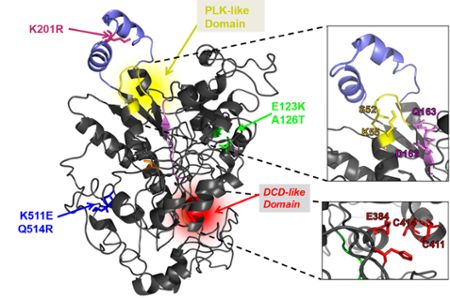

One gene discovered by Waters and his team was named DcdV. It's especially adept at defending cholera bacterium from cell-destroying therapeutic viruses called phages in that it hinders phages from replicating.

Understanding how DcdV prevents phages from multiplying may help researchers counter with the development of more effective phage therapy treatments for cholera and other antibiotic-resistant staph bacterial infections such as MRSA.

"We also found that DcdV is widespread in bacteria and even eukaryotic cells, like the ones found in our bodies,” Waters said. “There is a well-studied viral defense mechanism in humas called APOBEC proteins that defends again viruses such as HIV. It belongs to the same enzyme family as DcdV, suggesting a common viral defense function in bacteria and humans.”

Other researchers on the project are Janani Ravi, MSU Department of Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation; Kristin Parent and John Dover in the MSU Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology; MSU graduate student Brian Hsueh and former MSU graduate student Geoff Severin, Chris Waters lab; and Eva Top and graduate student Clint Elg, University of Idaho (through MSU's BEACON Center).

Banner image: Understanding how DcdV prevents phages (pictured above) from multiplying may help researchers counter with the development of more effective phage therapy treatments for cholera and other antibiotic-resistant staph bacterial infections such as MRSA.