MSU's Bruno Basso lands inaugural Morgan Stanley sustainability award

In the future of agro-ecology, a farmer’s profits won’t only be in what they grow above the soil, but also in what they put into it.

In an exciting collaboration between Bruno Basso, Michigan State University Foundation Professor, and Kristofer Covey, assistant professor of Environmental Studies and Sciences at Skidmore College in New York, farmers in the United States will have an opportunity to cultivate a sustainable future for themselves and the planet by adopting regenerative farming practices that increase organic carbon in agricultural soils and reduce greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere.

Their groundbreaking project, My Soil Organic Carbon, or MySOC, is a platform that measures soil carbon through app-led field methods, sophisticated remote sensing technology and biophysical modelling. MySOC was recently awarded a $250,000 prize from the Morgan Stanley Institute for Sustainable Solutions Collaborative.

In its inaugural year, the award initiates Basso and Covey into a global community of innovators that aims to address the world’s most complex global sustainability issues. Their winning project, along with just four others, will have an unprecedented opportunity to utilize Morgan Stanley’s vast networks and resources to increase the scale, impact and reach of their initiative.

"As the first agricultural technology school, regenerative agriculture is a key part of meeting our mission of research, education and outreach through the lens of our sustainability framework: campus, curriculum, community, and culture," said Amy Butler, director of sustainability at MSU. “This designation recognizes the global leadership and critical role that Dr. Basso, in partnership with his colleagues, serves in developing solutions to combat climate change and advance progress in the global United Nations sustainable development goals.”

“The prize is an honor, but it’s also such a gratification because this science can help farmers make a more informed decision about how to use regenerative farming to reduce emissions and store new carbon in the soil they can then sell on the market as offsets,” said Basso, a professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences in the MSU College of Natural Science and a member of the Long-term Ecological Research at W.K. Kellogg Biological Station. “It’s a new way of doing economics on the farm—money from the crop yield and money from protecting the environment.”

Three years ago, former Vice President and 2007 Nobel Peace Prize, Al Gore invited Basso to serve as a science advisor on his farm, Caney Fork, with the goal of demonstrating that agriculture could achieve net negative emissions through regenerative practices such as no-till, continuous cover cropping and pasture-raised livestock. Basso’s research showed a five-fold increase in carbon sequestration under those regenerative farming practices.

Using the Gore’s farm as their sandbox, Basso and Covey established MySOC’s parameters for satellite guided, strategic field sampling and streamlined the process for collecting those samples in the field and sending them for analysis to Will Brinton at Woods End Laboratories, another member of the Caney Fork Science Team. The data from MySOC samples will build a first-of-its-kind national soil carbon inventory.

“When Bruno and I met at Caney Fork, we pretty quickly realized that the combination of my experience planning rapid in-field and distributed measurement campaigns and his lab’s leading expertise in remote sensing and modeling was well-suited to solving the persistent challenge of assessing soil carbon at scale,” Covey said.

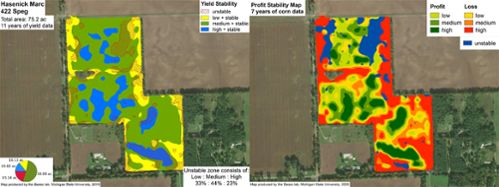

MySOC is one part of a larger suite of revolutionary technology under development in Basso’s lab to help reduce farmers’ financial risk when deciding how best to cultivate land. Through their unique algorithms from remote sensing imagery and crop modeling, they have already built subfield-level spatial analyses, meter by meter, of crop yield across the entire U.S. Midwest and can generate maps unique to each farm.

These “prescription” maps show farmers exactly what areas are generating greater environmental impact through fertilizer loss and low productivity, areas that instead could sequester marketable carbon through native perennials, bioenergy crops and cover crops while reducing greenhouse gasses associated with misapplied nitrogen fertilizers and other agrochemicals.

With this powerful tool in hand, literally as an app on their phone, farm profitability aligns with the fight against climate change, “where agriculture is a solution rather the problem,” Basso added.

“MySOC modelling provides the initial conditions and benchmarking of a geospatial common baseline to compare changes in carbon,” Basso said. “With the baseline carbon level established, farmers are incentivized to implement farming practices that increase soil carbon and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, making carbon credits available for companies to buy as offsets.”

Basso is not new to innovation. In 2016, he was the recipient of the MSU Innovation of Year Award for his breakthrough work on a digital systems approach for long-term sustainability and resilience of agricultural systems. This novel research led to the foundation of the Cambridge, MA based start-up, CiBO Technologies, a Flagship Pioneering company, with participation from Generation, an investment management company co-founded by Gore.

Basso credits the robustness of his models to the numerous contributions by many scientists, chiefly his former Ph.D. advisor MSU Emeritus Distinguished Professor Joe Ritchie, the unprecedented decades of data from MSU’s Long Term Ecological Research site and Great Lakes Bioenergy Center at the Kellogg Biological Station, the cherished collaboration with farmers and the work of his lab.

“In my lab, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and my lab’s success is the result of a diversity of international students, postdocs and programmers from different disciplines including agronomy, engineering, biophysics and computer sciences, to name a few” he said.

“I can never stop getting excited about how technology is bringing benefits to farmers who need guidance to reduce the risk they face when making decisions,” Basso added. “Soil sampling is not new, but now it can be inserted into a technology to quantify how much carbon they have and how to protect that carbon through farming practices that conserve it. Now they get paid by storing carbon as well as by selling grains.”

Banner image: Three years ago, former Vice President and 2007 Nobel Peace Prize, Al Gore invited Basso to serve as a science advisor on his Caney Fork Farm, shown here, with the goal of demonstrating that agriculture could achieve net negative emissions through regenerative practices like no-till, continuous cover cropping and pasture-raised livestock. Credit: Zach Wolf, Caney Fork Farm