Rare data link the effects of irrigation to the plight of farmland birds

As irrigation practices expand worldwide, many bird species face an uncertain future. Left with less nesting and foraging habitat and little to no fallow lands, many bird species that inhabit farmlands can have a hard time adapting. Fallow lands are lands left unplanted for at least one vegetative cycle and are also important to birds for food and breeding.

In a new paper published in Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, former Michigan State University visiting student Xabier Cabodevilla and his team found that 55 percent of common bird species in northern Spain decreased in their occurrence rates as a result of irrigation.

For Cabodevilla, who recently completed his Ph.D. in Spain, this paper is an extension of his work on human activity and its effects on biodiversity. In 2017, he met Elise Zipkin, an MSU integrative biologist and director of the Ecology,Evolution and Behavior (EEB) Program at the EURING Analytical Meeting in Barcelona and they began talking about a collaboration. In 2019, he joined the Zipkin Quantitative Ecology Lab for a 5-month internship to learn quantitative methods to enhance his research.

“Ecological statistics and modeling are not big fields in Spain, so I wanted to go abroad to learn cutting-edge techniques,” Cabodevilla said. “It was a great opportunity to intern with one of the best ecological modeling teams in the world.”

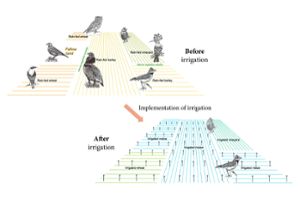

In the study, Cabodevilla and his team analyzed data collected at 19 sites throughout a 100 km2 area in Spain. With 13 years of data on the region’s 47 most common bird species, they had records in the area before and after irrigation was implemented. Cabodevilla studied how the bird community changed once the various sites were altered from rainfed to irrigated land.

“What makes this research unique is that it is serendipitously a Before-After-Control-Impact (BACI) study,” Cabodevilla said. “Since it is very difficult to know where irrigation will be implemented, ‘before’ data is almost always absent. It just so happened that irrigation was implemented in a region where Cabodevilla’s our and coauthor, Diego Villanua, had been collecting bird data for some years, so we were able to show how irrigation changed the composition and richness of local birds.”

Working with Spanish colleagues, Cabodevilla and the MSU team created models to analyze the BACI data. They used a hierarchical community model to estimate individual species occurrence probabilities at the sampling locations before and after the implementation of irrigation.These models, pioneered by Zipkin and her team for more than a decade, allow researchers to simultaneously estimate the responses of multiple species to environmental factors while also accounting for imperfect detection during sampling.

“Hosting visiting international students such as Xabier has had a tremendous impact on my lab, expanding the scope of our research and our collaborative network,” Zipkin said. “Xavier’s research examining the impacts of irrigation on avian diversity led to important results demonstrating the potential for negative effects on farmland birds as well as other local species – a topic that has been understudied.”

Cabodevilla believes that Spain is at a crucial moment because it is one of the Mediterranean and European countries with the least amount of agricultural intensification—the increase of agricultural productivity per unit of land. As agricultural intensification is being rapidly pushed across Spain, policy makers need to decide which way to go—full intensification, which comes with extensive environmental costs, or mediated approaches that co-prioritize biodiversity protection.

The hope is this paper will influence the European Union’s common agricultural policy toward conservation. When implementing irrigation systems, Cabodevilla recommends avoiding areas with high species richness or endangered species and maintaining diverse crops and environments to protect bird species when irrigation cannot be avoided. Farmland should include a mix of rainfed crops and fallow lands.

“We need to adopt clear environmental standards in these regions, if we, as society, want to maintain farmland ecosystems and the extensive biodiversity that they support,” Cabodevilla said.

Banner image: Three little bustards flying over fallow land next to the new irrigation system. The little bustard is endangered in the region and one of the species most affected by the implementation of irrigation. Credit: Diego Villanúa Inglada