The Ecological Stage: A new model links mate selection to species survival

In a new paper published in Ecology Letters, Michigan State University evolutionary biologist Janette Boughman shows that the process of choosing a mate could be very important to the survival of the species. To do this, she and co-author Maria Servedio introduce a new theoretical model they coin “The Ecological Stage.”

“It is great to be published in Ecology Letters because it reaches a large audience of ecologically minded evolutionary biologists and evolutionary minded ecologists,” said Boughman, professor in the department of Department of Integrative Biology in the MSU College of Natural Science. “Our model appeals to both theoreticians and empiricists. I’m hoping this model will help those who are trying to find out if sexual selection is helping speciation or hindering it, and to answer why it is working in one system and not in another.”

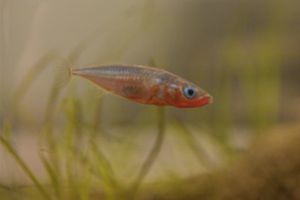

Mate selection and male display traits have been studied before, but no previous speciation model could fully explain why males have such diverse displays (e.g., bright plumes on birds or striking colors on fish) and why females are attracted to males with distinctly different displays. Boughman believed answering these questions could be evolutionarily significant to the concept of speciation, the formation of new species. She teamed up with Servedio, a theoretician from the University of North Carolina, to build and test a new model.

“I’m mostly an empiricist, so I like my theory to be grounded in reality,” Boughman said. “The way this model is constructed with two environments for the different traits and two for female preferences, is a bit more complex and more biologically realistic than what has been done.”

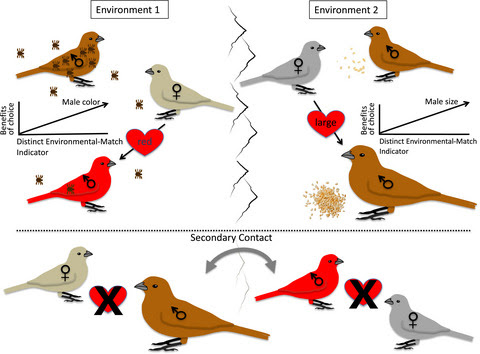

The Ecological Stage model is based on two closely related species that have been separated into two different environments. For example, environment one is full of parasites, therefore high parasite resistance leads to high fitness and a red body color. The females prefer red males because parasite resistance is beneficial both to them and their offspring. In environment two, individuals compete for food. Those able to forage well have higher fitness and therefore, larger bodies. Females in this scenario prefer larger individuals. In both environments, the females’ choice of mate will increase their own and their offspring’s fitness.

In the second part of the model, the related species come back into proximity, a phenomenon known as secondary contact. In theory, the two species could then start to hybridize, or crossbreed, a process that can lead to the extinction of the two distinct species. However, In Boughman’s model the species do not hybridize. Females continue to select males with traits that are adaptive to the local environment. In the model, the females in environment one still prefer red males over large males after secondary contact, while females in environment two still prefer large males over red males. The Ecological Stage model reveals there may be an underlying biological reason protecting the two distinct species.

“Before we built the model, I was convinced that because different genetic positions controlled the different preferences in this scenario, both preferences would spread universally across both populations. For example, all females everywhere would prefer large, red males,” Servedio said. “But this wasn’t what we found. We were able to maintain preference divergence, meaning one population predominantly preferred red and the other predominantly preferred large. This really surprised me.”

Different and changing environments is at the heart of Boughman’s current work as she tries to understand how organisms adapt or don’t adapt to global change. Whether sexual selection is helpful or hurtful to speciation is still controversial, yet The Ecological Stage model can provide some answers. The model shows how sexual selection can be helpful to speciation and diversification. If populations impacted by climate change are now in separate locations and have adapted to their new environments, then the ecological stage could come into play. Individuals in one location may not be able to mate with individuals in the other population even though they could not long ago.

Banner image: Related species offer differ conspicuously in displays that males use to attract mates and that females prefer - more so than in most other traits. In the first pheasant species females prefer bright plumage while in the other females prefer large body size.