Working to stop the spread of breast cancer

Michigan State researchers are revealing the molecular workings of how a certain form of metastatic breast cancer spreads to other parts of the body. In doing so, they’re creating new ways to spot and contain what is called triple negative breast cancer.

We focused on triple negative breast cancer, or TNBC, because it occurs proportionally more often in younger patients and has worse clinical outcomes,” said Sophia Lunt, an associate professor in the MSU College of Natural Science.

“The vast majority of TNBC-related deaths are due to metastasis, the spread of cancer cells from the primary tumor to other sites in the body,” Lunt said. “Metastatic breast cancer is not curable, and available treatments aim to only slow disease progression.”

Since joining MSU in 2015, Lunt’s research has focused on understanding the role of metabolism — which nutrients and compounds cancer cells use and how — in metastasis. She and her team are now reporting results from their work on triple negative breast cancer, so named because its tumor cells test negative for three types of proteins used in diagnoses.

Lunt’s latest research, funded in part by a new $2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, is published in the journal Nature on May 18.

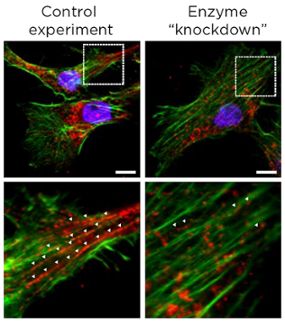

In the Nature paper, the Spartans were part of an international team that showed cancer cells with low levels of the enzyme phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase, or PHGDH, posed a greater risk of spreading.

The result was surprising at first, Lunt said, because cancer cells also use this enzyme to multiply. The more of the enzyme a tumor has, the more likely it is to grow. Yet, lower levels help a tumor spread. This finding was supported by data from human breast cancer patients as well as additional studies in cancer cells and mouse models.

“We initially expected high PHGDH expression to support both proliferation and metastasis,” said Lunt, whose lab is in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

“However, the results make sense because cancer cells' needs during proliferation and metastasis are very different,” she said. “During proliferation, cancer cells want to divide as fast as possible in a familiar environment. During metastasis, cancer cells have to survive the extremely stressful process of leaving the primary site, traveling through the bloodstream, finding a new site and surviving in an unfamiliar environment.”

When tumors reduce the abundance of the PHGDH enzyme, other enzymes and the processes they orchestrate can step to the fore. In the case of triple negative breast cancer, one result is the production of sialic acid. The acid helps cancer cells adhere to other cells and components of biological tissue during metastasis.

Probing the molecular mechanisms that underlie this cascade of reactions and interactions is the goal of Lunt’s new $2 million grant, announced in March by the National Cancer Institute.

Unraveling cancer’s intricate and tangled biochemistry is challenging, but Lunt is showing how joining and growing a global network of experts can help overcome obstacles in this field.

“Biology is extremely complicated with countless variables and players,” Lunt said. To counter that, “teamwork, collaboration and funding are essential,” she said.

Lunt first met collaborator Sarah-Maria Fendt, a cancer researcher in Belgium, when they were both postdoctoral researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

But it wasn’t until Fendt saw Lunt give a 2019 seminar on sialic acid biosynthesis at an international conference in Florence, Italy. That collaboration ultimately included researchers from more than 30 departments across three continents.

“I think large collaborations like this are becoming more common as we integrate datasets from multiple levels and use specialized techniques,” Lunt said.

This collaboration included Shao Thing Teoh, who was a postdoctoral researcher in Lunt’s group and is now a project scientist in Austria. When he joined Lunt’s lab in 2016, he helped the team begin investigating metabolism in metastatic breast cancer. Now, Lunt and the next generation of her group’s researchers will continue that work with their new grant.

These Spartan projects are revealing new molecules that could be assessed by doctors in the future to determine the risk posed by tumors. The research also creates footholds for drug developers to exploit while developing new ways to attack cancer.

“Our studies could lead to new biomarkers — such as low PHGDH and high sialic acid — that determine metastatic risk and to novel therapeutic targets for patients with metastatic TNBC,” Lunt said.

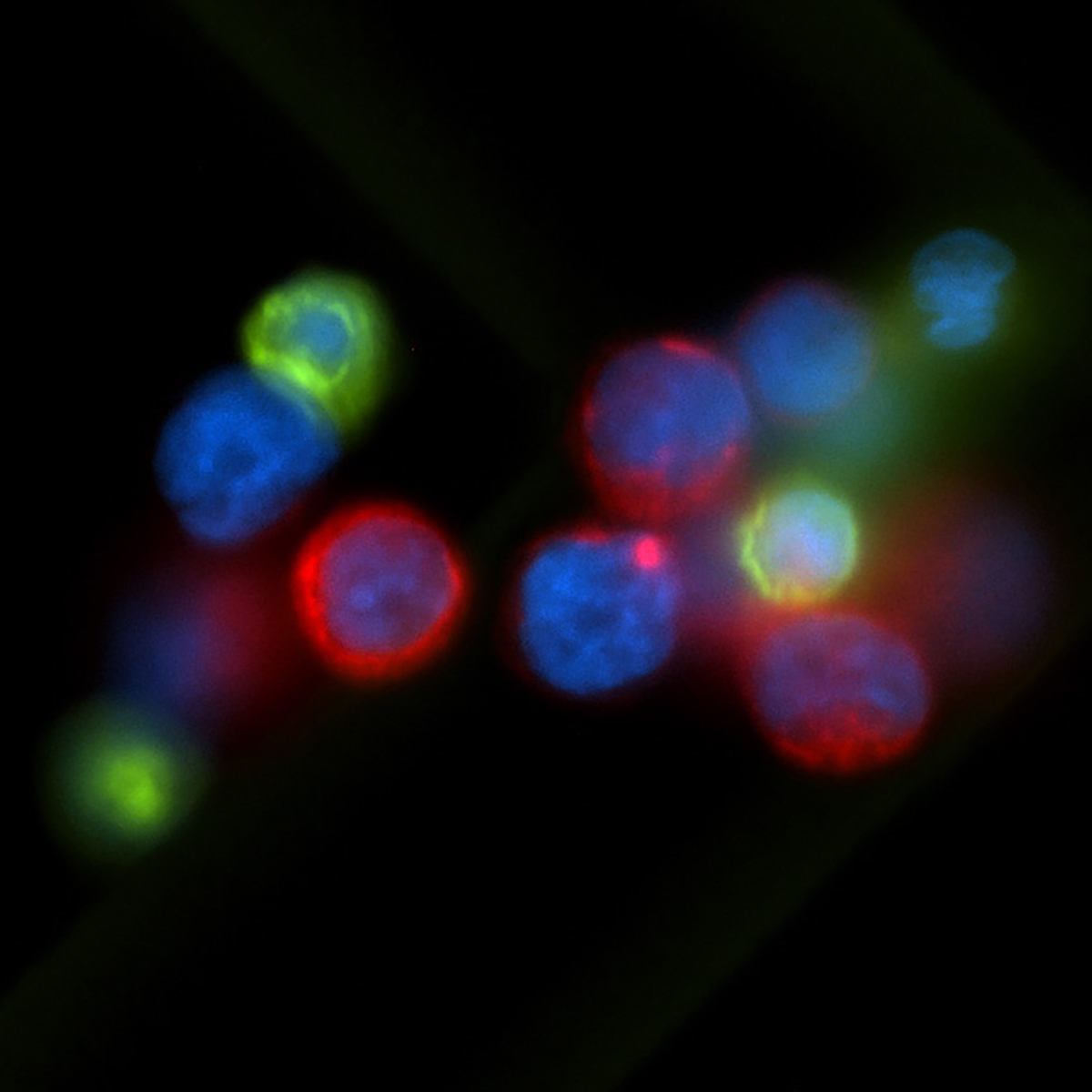

Banner image: MSU researchers are unveiling and studying chemical clues that could lead to better diagnoses and treatments for a metastatic form of breast cancer with support from a $2 million NIH grant. The micrograph above shows cancer cells (red) found circulating in the blood of a breast cancer patient. Credit: National Cancer Institute/USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center/Min Yu