MSU research supports lifting the weight of physics GRE in admissions

Currently, more than 200 students are enrolled in MSU’s Department of Physics and Astronomy graduate program and like most applicants across the country, the physics hopefuls were required to take the physics Graduate Record Examination (GRE) to get there. The test costs just over $200, is administered early Saturday morning and requires the prospective student to answer 100 rapid fire questions in just 3 hours.

According to the physics GRE website, the money and time are worth it. Doing well on the test will help students stand out like a diamond in the rough among the thousands of other applications being sifted through admissions committees buried in them.

But will it?

New research published by Nick Young, fourth-year graduate student in the Department of Physics and Astronomy and the Department of Computational Mathematics, Science, and Engineering (CMSE) and his advisor, Danny Caballero, associate professor and co-director of the Physics Education Research Lab, used rigorous statistical models to analyze data on this important question and the answer, supported by the data, was no.

Their results were recently published as an Editor’s Suggestion in Physical Review Physics Education Research.

“My graduate research focuses on graduate admissions in physics departments and one of the assumptions is that if you do really well on the physics GRE it could compensate for doing poorly in a different area, like GPA, because it’s given a lot of weight,” Young explained. “But no one has actually really tested that. They just assumed it was true.”

Since 1936, the GRE has been used, along with GPA, as one of the main instruments for measuring how well a student might do in graduate school. But Young pointed out that the demographics of physics graduate students has changed very little over the last few decades, even as other sciences have diversified, becoming less white and less male.

Taking a hard look at how relying on ubiquitous tools such as the physics GRE might not benefit some students is key to increasing equity and diversity in graduate school admission.

“One of the major trends that you observe across physics graduate programs is that institutional biases including systemic sexism and racism exclude incredibly capable students from entering and succeeding in graduate physics programs,” Caballero said. “Nick’s research helps us to understand how the physics GRE contributes to those biases starting with the mismatch in the GRE’s messaging and its use by graduate programs. Asking students to spend a couple hundred dollars to take this test in order to even apply to some graduate programs is a travesty.”

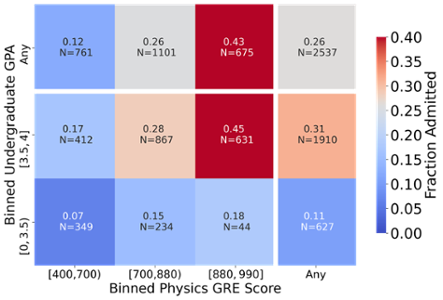

The researchers tackled the problem in two parts. First, they separated undergraduate student GPA into incremental bins to parse out the overall influence of GPA on GRE scores and ultimately being admitted to a graduate program. Next, they developed robust statistical models to determine what might be affecting the relationship between GPA, test scores and admission, such as school size.

Young and Caballero concluded that rather than help, taking the physics GRE could actually harm a student’s chances of admission.

“If this test is really helping you stand out, doing well on the test should be better than doing bad and having high grades, but that wasn’t the case,” Young said. “We found that most students will not benefit by taking the test. In fact, for every 1 student who could possibly benefit from the test because they had a low GPA but did really well on the test, there were 9 students in the opposite situation, who had a high GPA but very low GRE scores, hurting their chances of admission.”

The scientists considered the role of gender and race, but the programs they used for the study—five universities across the Midwest and East coast totaling 2,500 graduate students—were all actively working to change their admissions process to increase diversity, clouding the ability to accurately measure these variables.

Still, results from the seminal paper will give admissions committees food for thought as they continue to wrestle with how choose students that will likely do well in their programs.

“The college board, the SAT and the ACT all have huge power over admissions, but as researchers we need to consider if what they say is actually true or just marketing claims by businesses who have a stake in it,” Young said. “As scientists, we require evidence in our research, and so should these organizations. Are these tools supposedly helping us in admission actually doing so, or is it a barrier for students to have to pay a few hundred dollars for a test that’s not providing any useful information?”

Young began his graduate studies at MSU four years ago, when the Department of Physics and Astronomy was just beginning to undergo changes in admissions to bring in more women and people of color. He is most excited about being a part of that process. In fact, his dissertation is based on it.

“My thesis compares the approach of the program before I arrived and after, and it is promising that our three years of evidence leans in favor of positive change,” said Young, who is traveling down the interstate after he graduates for a postdoctoral position in educational data science at the University of Michigan. “Instead of being in between physics education and CMSE, I’ll be directly in the middle of it. I’m super excited about it.”

Banner image: The $200 physics GRE asks students to answer 100 multiple choice questions, like these, in just three hours and claims it will help them stand out among other applicants. But new research by MSU scientists does not support that claim. Credit: Pixabay