Fighting COVID and future diseases

The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services is enlisting experts and resources at Michigan State University to bolster the state’s fight against COVID, foodborne illnesses and more.

With three grants totaling more than $5 million, MSU and health care partners will help build up Michigan’s capacity to respond to the current pandemic and future pathogens. MDHHS created what it calls the Michigan Sequencing Academic Partnership for Public Health Innovation and Response, or MI-SAPPHIRE, with federal funding from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The goal of the program is to “address emerging disease threats and enhance the state’s ability to respond to those threats,” MDHHS announced.

The MSU and MI-SAPPHIRE partnership will tap into resources already primed to contribute, including MSU’s Genomics Core, Veterinary Diagnostic Lab and relationships with communities and health service providers across the state. It will also help train a new generation of experts and technicians who will combat the next threat to public health.

MDHHS awarded a total of $18.5 million in MI-SAPPHIRE grants to four state universities: MSU, the University of Michigan, Wayne State University and Michigan Technological University.

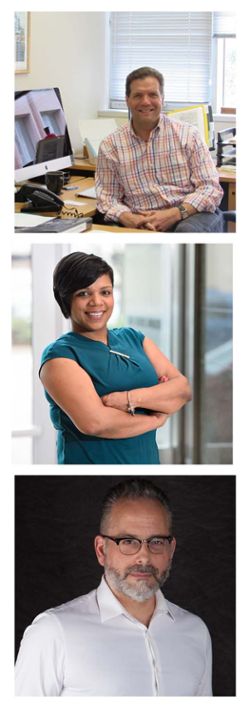

“The MDHHS grants build on the scientific expertise of our research teams and further support our efforts to add capacity to address public health issues,” said Doug Gage, vice president for Research and Innovation. “Our recent investments in core facilities and key faculty hires in areas such as bioinformatics and infectious disease align very well with not only MSU’s goals, but with the state’s desire to have teams prepared to preemptively take action. I’m confident MSU and the state’s public universities are ready to serve in this capacity.”

Expanding coronavirus surveillance

One of the grants, worth $1.87 million, will leverage the sequencing tools and expertise found in MSU’s Genomics Core at the Research Technology Support Facility to help spot and track coronavirus variants that emerge after delta and omicron.

It’s easy to see how an MSU facility with decades of experience and state-of-the-art instruments would be an asset to the state, helping monitor the precise genetic identity of coronavirus infections detected in Michigan. What may be more surprising to learn is that Spartans who don’t have access to next-generation gene-sequencing tools will be lending a hand, too. Or, more accurately, lending some saliva.

As part of the grant, the Genomics Core will begin sequencing viruses detected in positive samples by MSU’s Early Detection Program, better known to the students, staff and faculty who use it as the Spartan Spit Kit.

Previously, when the Early Detection Program, or EDP, identified saliva samples testing positive for coronavirus, MSU would send those samples to MDHHS. The state health agency would then sequence the viral genomes found in those samples to determine which versions of the SARS-CoV-2 virus were present in the MSU community. Now, whole-genome sequencing will be done using the tools and expertise of the MSU Genomics Core, boosting the state’s virus sequencing and surveilling capacity.

The Early Detection Program provides an established source of coronavirus samples that will be augmented by building connections with other existing testing programs. Last year, CDC awarded MSU researchers $6 million to help close racial gaps in vaccination rates, in part, by working with medically underserved communities in Flint and West Michigan. Now, with support from MI-SAPPHIRE, MSU will be able to sequence viruses detected in those communities.

Thanks to MSU’s partnerships with Michigan health systems, researchers will also have access to coronavirus samples discovered in immunocompromised patients in the state’s hospitals. And, working with experts in its Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, MSU will be able to sequence coronavirus samples obtained from animals.

“These are unique features of our MI-SAPPHIRE program that highlight the breadth of research strengths at MSU and take advantage of the investments made in the past two years in the EDP,” said Victor DiRita, one of the leaders of the project. DiRita is the Rudolph Hugh Professor and Chair of the College of Natural Science’s Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics. “We are expanding our understanding of viral sequence diversity tremendously with this grant.”

By sequencing more viruses from more sources, Spartan scientists will help better understand how novel coronavirus variants evolve and help identify them sooner.

“Sequencing technology and our knowledge of rapid pathogen evolution are coming together beautifully as we follow COVID,” DiRita said. “Programs like MI-SAPPHIRE help build the infrastructure to ensure we are keeping pace with the evolutionary changes occurring.”

“The state is saying let’s use the experts and expertise of the universities within the state. Let’s build up an infrastructure that uses MSU, U of M, Wayne State and Michigan Tech,” said Jack Lipton, architect of the EDP and a co-leader of MSU’s $1.87 million MI-SAPPHIRE award. Lipton is also chair of the College of Human Medicine’s Department of Translational Neuroscience.

“Then when the next pathogen comes around, you have the infrastructure in place,” Lipton said. “The state is building for the future and, in the process, answering questions for today.”

Completing the leadership team with DiRita and Lipton on the project is Debra Furr-Holden. Furr-Holden is also the leader of the $6 million CDC grant and the C.S. Mott Endowed Professor of Public Health, a professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics and director of the Flint Center for Health Equity Solutions.

The team has also enlisted Spartan experts from across the university. This includes Kevin Childs, director of the Genomics Core and an assistant professor in the Department of Plant Biology; Brett Etchebarne, an assistant professor in the Department of Osteopathic Medical Specialties and an emergency medicine specialist with Sparrow Hospital; and doctor of veterinary medicine Kimberly Dodd, director of the Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory in the College of Veterinary Medicine.

“These transdisciplinary teams are exactly what this pandemic and much of our public health work needs,” said Furr-Holden, who also serves on the Michigan Coronavirus Task Force on Racial Disparities created by executive order of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer. “This effort to identify and understand the spread of COVID and new variants within medically underserved communities will strengthen our capacity to give communities the knowledge and tools to fight back.”

Boosting bioinformatics

Of course, detecting and sequencing more viruses is just one part of surveilling the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and trying to stay a step ahead of its variants. The state will also need the ability to analyze, understand and disseminate all of the data it’s gathering. In the context of health and biological sciences, solving these big data problems is referred to as bioinformatics.

Bioinformatics is a core component of another MI-SAPPHIRE grant, worth a total of $2.5 million, that has MSU working with Spectrum Health. Part of this investment will bring Spectrum Health West Michigan’s array of sequencing tools to bear in the fight against COVID. Another part, about $600,000 of the grant, will have Spartans leading an effort to ensure the state has the computational resources it needs to make the most of the data it collects.

“Our project is critical as we are unique in focusing on developing new computer tools for this pandemic and other viruses,” said Jeremy Prokop, an assistant professor in the College of Human Medicine who was recruited to MSU in 2018 as part of the Global Impact Initiative. “We want to launch new tools that can be used by everyone to quickly take sequence data of a viral genome and know if the differences correlate to strains of the virus, like omicron, or if new variants will alter the function of the virus and could be of major concern.”

These new tools will not only help detect, track and better understand future variants, but help prepare for future viruses and pathogens, said Prokop, who works in the Department of Pediatrics and Human Development and Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology.

“As we get past COVID, our goal is to also build these tools for other pathogens that could one day be pandemic,” he said.

Through the grant, Prokop’s team will also train undergraduates across the state in bioinformatics skills needed to develop and implement such tools. In preparing for the future, the state isn’t just focused on new tools and technologies, it knows it will need a workforce who knows how to use them.

This feature highlights the common thread between MI-SAPPHIRE projects. Michigan is tapping into the expertise it has in-state to build up infrastructure that will help serve and protect its residents now and into the future. Another key component of that, Prokop said, is building bridges between the state’s experts in health care, government and state research institutions.

“The projects are about bringing state, academic and medical resources together. The pandemic has highlighted the challenges of communication,” Prokop said. He and his team are a natural choice to help facilitate those connections, having published over 30 scientific papers with Spectrum Health since joining MSU.

The MI-SAPPHIRE grant will ultimately result in better care for patients, which the teams are working to demonstrate with its grant. “Just like with the human genome, understanding genetic details of the virus can transform our care for each patient,” Prokop said.

Focusing on foodborne pathogens

MSU’s third MI-SAPPHIRE grant does not directly support the state’s coronavirus response, but it is still very much in line with MDHHS’s goal of being best prepared for health challenges occurring now and in the future. Shannon Manning, a MSU Foundation Professor in the College of Natural Science, has received a $1 million grant that will support her team’s efforts to monitor Michigan’s foodborne pathogens and address the unique challenges they present.

“Because we have unique geographical features and agricultural systems in Michigan, it’s not surprising that different pathogenic bacterial strains may survive better here than elsewhere,” said Manning, who works in the Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics. “We also see high rates of antibiotic resistance in these pathogens, which is a very important problem globally and limits our ability to treat these infections.”

Although COVID is the state’s — and the planet’s — most pressing health concern, other pathogens are still out there, doing what pathogens do: infecting people and evolving countermeasures to how people fight them. This includes foodborne pathogens.

“Most of the foodborne disease trends that we know about in the U.S. come from the CDC FoodNet surveillance system. The problem is that Michigan is not part of that network,” Manning said. “Through this grant, we will better define the genomic traits of key foodborne pathogens circulating in the state and develop new methods to detect them. This collaboration is important to fully understand disease trends in Michigan.”

This is another grant that exemplifies how the state is leveraging existing expertise and relationships to bolster its preparedness. Prior to joining MSU, Manning was a research fellow at MDHHS who helped establish a hospital-based surveillance system throughout Michigan for Shiga toxin-producing E. coli or STEC (not all forms of E. coli make people sick, but STEC strains are one of the harmful varieties). This work was supported by the CDC and the Association of Public Health Laboratories.

Because of this long-standing collaboration with the MDHHS, Manning and her team have over a decade of experience at MSU, studying and monitoring pathogens that can contaminate food and lead to illness, hospitalization and even death. This includes the bacterial pathogen STEC as well as salmonella, shigella and Campylobacter jejuni, which are all leading causes of diarrheal disease in the state and country.

The Manning Lab is also showing how certain bacterial genes and pathogen-human interactions can help fuel antimicrobial resistance. The team’s MI-SAPPHIRE grant will help support the genetic surveillance of enteric pathogens in the state while bolstering the researchers’ ability to keep pace with emerging trends in foodborne illnesses.

For example, the grant will help Manning forge connections with MSU’s Veterinary Diagnostic Lab to analyze pathogens from livestock and other animal sources, which could help develop diagnostics for more rapidly detecting these pathogens before they reach humans. Similar to the other MI-SAPPHIRE grants, using and expanding the Spartan team’s unique tools and talents will help better protect Michigan residents now and into the future.

“Performing long-term genomic epidemiological studies are quite expensive and require a large research team with specialized skills,” Manning said. “This grant will allow us to build up our team and skill set and provide new ways to work alongside the MDHHS to positively impact public health.”

Banner image: Spartans will help protect Michigan’s health with several millions of dollars in support from the state and the Centers for Disease Control. With three grants totaling more than $5 million, MSU and health care partners will help build up Michigan’s capacity to respond to the current pandemic and future pathogens. Credit: